Is the USGA going to set up Pinehurst extra hard because of low scores in recent majors? – Australian Golf Digest

- by Admin

- June 9, 2024

There was nothing subtle about the way Winged Foot was set up for the 1974 U.S. Open.

The USGA took what was already one of the hardest courses in the country and grew shin-tickling rough defending champion Johnny Miller said ranged from six to 10 inches high. “I like to measure U.S. Open rough by how far you’d be able to advance 100 balls if you hit into 100 different lies,” he said for Golf Digest’s oral history of the 1974 U.S. Open. “Some recent courses haven’t had any rough to speak of. At Winged Foot in ’74, the average was 80 yards. All you did was hit wedge or sand wedge out.”

And the greens? A car drove across the first green early in the morning before play on Friday and left visible tire tracks in the dew. Once the grass was cut, there was no sign anything had happened. Players could hear their approach shots hit the concrete-like greens from 175 yards away.

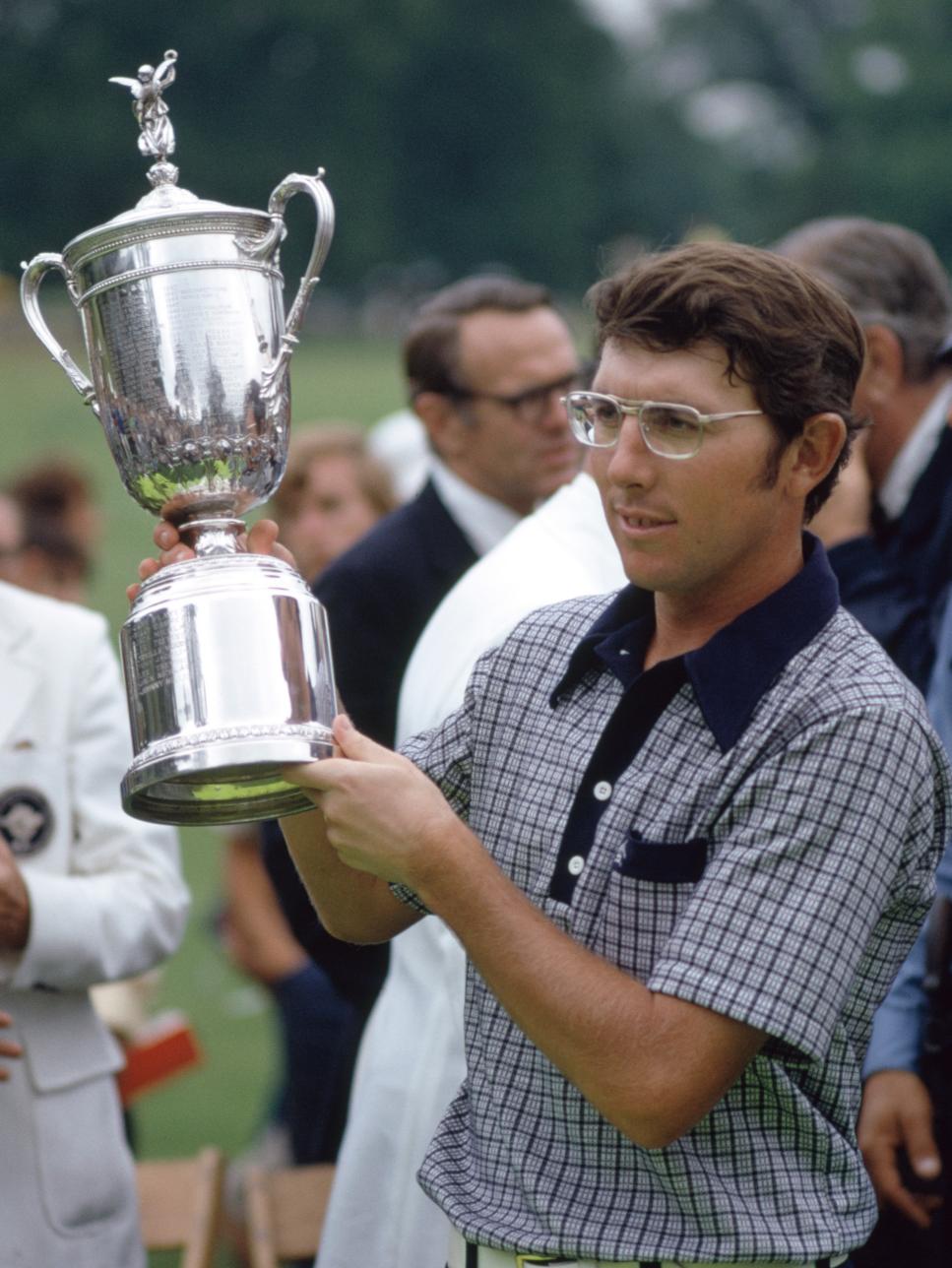

The conditions were reflected in the scoring: Hale Irwin’s seven-over-par total was the highest winning score by a champion in 40 years, and the event earned the nickname “The Massacre at Winged Foot.” Irwin and Miller were among many competitors that week who called the setup the most brutal they had seen. Tom Weiskopf acidly referred to Miller’s record-low final round the previous year at Oakmont as the USGA’s motivator for fully exposing Winged Foot’s fangs. “It was pretty obvious after 1973 that we were going to get the conditions we played under,” he said. “It was a typical knee-jerk reaction by the USGA.”

Hale Irwin won the 1974 U.S. Open at Winged Foot with a score of seven over par. It was the highest winning score by a champion in 40 years, and the event earned the nickname “The Massacre at Winged Foot.”

Leonard Kamsler/Popperfoto

Not everyone hated the hardness. Jack Nicklaus waxed misty about the old days from the podium at The Memorial this week. Nicklaus has relentlessly modified Muirfield Village Golf Club, a course he designed, to make sure it plays hard enough. “I used to like the course setups the way the USGA did, where you had 25-yard fairways or whatever and you had, you know, three, four inches of rough, and then you had high rough,” Nicklaus said. “By gosh, there was no mistake; you either hit it in the fairway or you struggled. I liked that. I like greens where you got to send the ball up in the air and bring it down like, as they say, a butterfly with sore feet. You got to be able to play that way. That’s what I enjoyed. But you know why I enjoyed it? Because I could do it. When you could do something that somebody else couldn’t do, then you enjoy competing in that type of a situation.”

Fifty years later, on the eve of this year’s U.S. Open at Pinehurst No. 2, almost everything has changed—including the USGA’s philosophy surrounding a course’s playing characteristics. If the 1974 setup was done with a machete, the work is now being done with a scalpel. In the months leading up to the event, the USGA and the home-course maintenance team have been practicing the kind of plastic surgery popular with A-list actors: build an enhanced and authentic-looking version of what was already there and give a variety of playing styles a chance to win.

The proof is in the recent list of champions, the scores they shot and the way the events have been received. Since the last U.S. Open at Pinehurst in 2014, only one champion has been over par for the week. Brooks Koepka was one over par at Shinnecock in 2018, defending his title a year after scorching Erin Hills at 16 under par. The winning score the past five years has averaged eight under par, including last year’s 10-under-par performance by Wyndham Clark in a week in which two players (Xander Schauffele and Ricky Fowler) shot 62. Champions have ranged from bombers (Bryson DeChambeau) to stylists (Matt Fitzpatrick) and World No. 1s (Jon Rahm) to up-and-comers (Wyndham Clark). Television ratings were up more than 20 percent last year in an environment in which more than 10 percent fewer households are tuning in to traditional television.

Instead of obsessing about making Pinehurst punishingly hard in response to relatively low scoring last year (or last month, when Schauffele went 21 under at the PGA Championship), the stated goal is to make Pinehurst No. 2 play as the fairest, most substantial version of itself—and present in a way original designer Donald Ross could recognize.

Pinehurst No. 2, site of this year’s U.S. Open, is ranked No. 29 on America’s 100 Greatest Golf Courses. The USGA says it wants to make the course play as the fairest, most substantial version of itself.

Stephen Denton

“We could have a cookie-cutter approach and try to put our thumbprint on it, but we don’t do that,” said John Bodenhamer, the USGA’s chief championships officer. “Our golf-course-setup philosophy is to take America’s greatest venues and let them be what they were intended to be for the world’s greatest players and let them showcase their skills. We want every club in the bag to get dirty. We want them to hit it left to right, right to left, high and low. We want to challenge their mental aspects and their physical aspects. It’s that simple.”

Pinehurst No. 2 is on the other side of the country from the North Course at Los Angeles Country Club and at the other end of the design spectrum. LACC offered plenty of room off the tee, wiry bermuda rough and unplayable barranca areas. Pinehurst No. 2 has no mowed rough, just wild areas where superintendent John Jeffreys and his team have strategically planted more native wiregrass to frame expected landing areas and punish wayward shots. That makes the visuals much different than the U.S. Open of 10 years ago when the Ben Crenshaw and Bill Coore renovation was still brand new.

When conditions in the weeks leading up to the tournament are benign and predictable—as they have been this year in Pinehurst—tournament staff can control grass heights to a hundredth of an inch and deliver water with a similar level of precision. “We get that maybe once every five years for a U.S. Open, where it comes down to just three things,” said former USGA executive director Mike Davis, who oversaw the setup at the previous Pinehurst U.S. Open in 2014. “You’re managing your mowing heights, and if you’re lucky enough, you manage the water. They’re reading moisture levels on every green quadrant; they’re taking firmness readings. We look at all kinds of data, and that gives the plan for that afternoon or that evening’s prep. Then we’re monitoring Mother Nature.”

Better technology—and more openness to considering “playability” as a priority—has helped avoid disasters like the one at Shinnecock in 2004 when the USGA lost control of the course on Sunday after unexpected heat and wind. Crews were forced to syringe the seventh green between groups to keep the grass alive, presenting wildly different playing conditions for groups before and after the moisture was added. No venue has as much control as Augusta National does with its extensive SubAir system and army of groundskeepers, but Pinehurst No. 2 is down the street from USGA headquarters, and the course has been closed since late February to get ready for its big date. Lack of attention to detail—or time—will not be an issue.

At Shinnecock in 2004, USGA officials were trying for firm and fast conditions, but the baked-out course got away. Complaints began in the first round but escalated on Sunday when the seventh green required watering throughout the day to make sure it would survive. The scoring average for the final round was 78.7.

Jim Gund

Weather is still obviously a wildcard: A chance of rain is predicted for Wednesday and Thursday in Pinehurst, and then the forecast turns sunny and hot. At the PGA Championship, nobody thought Valhalla was going to play hard, but soaking rain and perfect greens meant it quickly turned into a track meet. Still, the caliber of the leader board and exciting finish was proof the venue still did its job of identifying the best player. Exhaustive contingency planning for potential weather outcomes—and almost a year closed to members to get ready—meant the pivot was seamless.

There’s no great historical performance parallel for Pinehurst even though three men’s U.S. Opens and a women’s U.S. Open have been played here in the past 25 years. The events Martin Kaymer and Michelle Wie won in back-to-back weeks in 2014 were early in the course’s life as a restored version of its classic self. Michael Campbell and Payne Stewart won on courses even more different than this one. Kaymer won in an eight-stroke laugher over Rickie Fowler and Erik Compton. Wie beat Stacy Lewis by two shots, and Michael Campbell was the beneficiary of Retief Goosen’s final-round collapse and ended up beating Tiger Woods by two shots. The best of them all is the 1999 edition, when Stewart made a 15-footer on the last hole for par that kept him one shot ahead of Phil Mickelson.

He was the only player under par for the week.

As USGA competition chairman Sandy Tatum said during the Winged Foot Massacre, “We’re not trying to humiliate the best players in the world. We’re just trying to identify who they are.”

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com

The Latest News

-

December 26, 2024Australian travel vlogger finds the ‘best alcohol on the planet’ in India | – Times of India

-

December 26, 2024What Emma Navarro has done before the Australian Open which has really impressed Jon Wertheim

-

December 26, 2024“Not what I wanted” – Halep withdraws from Australian Open 2025 due to injury

-

December 26, 2024Texas Freshman Tennis Star Maya Joint To Turn Pro Ahead Of Australian Open

-

December 26, 2024Injured Halep forced to pull out of Australian Open