Who Is Payne Stewart? – Australian Golf Digest

- by Admin

- October 22, 2024

Twenty-five years after the Payne Stewart passing, a writer remembers unguarded times.

The neighbourhoods around Bay Hill Club in Orlando, Florida, are notoriously maze-like, and on a March morning in 1999, I couldn’t find Payne Stewart’s house. He lived just off the 12th tee of the course, and I’d been to his home before, but somehow was looking on the wrong side of the street. Suddenly a barefoot guy in shorts and a t-shirt sprang into the street and slapped the hood of my rental car, waving his arms and yelling as though warning of a washed-out bridge. It was Stewart, of course, as theatrical and extroverted as you saw on TV. When Stewart comes to mind, I don’t see the celebration when he holed the putt on the final hole at Pinehurst to win the 1999 US Open. I see that snippet of him in his natural habitat three months earlier, waving his arms and laughing as he shouted through my rolled-up window, “Right here, dummy!”

Interview gold came from Stewart that day, as it always did with him, and I left thinking I’d hang with him many more times. But a few months and his best career exploits later, he was gone. It’s been 25 years since the Learjet 30 carrying Stewart and five others – pilot Michael Kling, 42; first officer Stephanie Bellegarrigue, 27; course architect Bruce Borland, 40; Stewart’s manager, Robert Fraley, 46 and one of Fraley’s colleagues, Van Ardan, 45 – plunged into a field near Mina, South Dakota. It occurred on October 25 after a catastrophic loss of cabin pressure not long after takeoff. They were travelling from Orlando to Dallas, where Stewart was consulting on a course design in nearby Frisco. From there they were headed to Houston for the Tour Championship. All were probably rendered unconscious within a minute or so, and the plane drifted north and eventually ran out of fuel.

It stands as the saddest moment in golf. That Stewart was happily married to Tracey, his wife of 18 years, and had two wonderful children – daughter Chelsea, 13 and son Aaron, 10 – made the tragedy even more heartbreaking. Media coverage was extraordinary, with national TV networks interrupting daily programming to cover the episode live well before the plane crashed. Jim Nantz, then as now a CBS sports broadcaster, hustled from a restaurant in Connecticut to New York City to assist in reporting for the network. The immediate aftermath was morose but inspiring, the long-term appreciations stunning and prolonged. Stewart’s funeral in Orlando five days later was attended by many of the most noteworthy people in golf. Jackie Burke, the great golf sage who passed away at 100 earlier this year, once said, “Live your life so that when you die, you fill up the church.” First Baptist Church in Orlando was packed that day. Eight months later, at the 2000 US Open at Pebble Beach, some 40 tour pros simultaneously blasted golf balls into the Pacific Ocean in tribute. Documentaries, books and dozens of articles followed. We saw plenty of tributes to Stewart during the US Open at Pinehurst earlier this year – and more will follow.

We’re still talking about Stewart, and it sometimes feels like he’s still here but standing just off-stage. It’s important to remember that a whole generation knows him only by reputation and highlights on YouTube. The Stewart catalogue thankfully is substantial. He was known for his gorgeous, old-school, athletic swing; the explosive, knickered outfits that sometimes looked elegant; the spontaneous, one-of-a-kind reactions when a big putt fell; the furious gum-chewing; the sawed-off Missouri twang; the physicality when he hugged his children or his caddie, Mike Hicks; and the way he cradled Phil Mickelson’s face after defeating him at Pinehurst. Stewart was as distinct as any player who ever lived and a truly exceptional one. He won three majors, the 1989 PGA Championship and the US Open in 1991 and 1999. He won 11 PGA Tour titles overall, played on five US Ryder Cup teams and finished second in two Open Championships. We wonder what he would have done had he been able to keep going. That long swing and ageless flexibility suggest great things, but he also had three degenerative disks in his lower back and an enlarged heart. It’s a mystery, but fans certainly would have paid good money to find out. Stewart was, as the late writer Dan Jenkins frequently pointed out, a “ticket seller”. He put bums on seats. He made the game better.

Who was Payne Stewart, really? I had several longish sits with him over the years. Not enough to become close but enough to where he would deliberately bump into me and knock me off balance and then say, “Oh, I’m so sorry.” The last visit in 1999 was the most revealing, and I’ll reference it because it mirrors the impressions of others. He demonstrated both tremendous hospitality and simple generosity. When we talked about his latest outfits, he showed me his closet, a mini-department store packed with shirts, shoes, hats and a long row of knickers/plus-fours. “You want a pair?” he asked. I stupidly declined. When we talked about music – his beloved set of harmonicas and performances with buddies Peter Jacobsen and Mark Lye in their novelty group, Jake Trout and the Flounders – he quickly dashed off to get a CD for me. That, I accepted. He also offered to make lunch. He just liked to give people stuff. When Stewart won at Bay Hill in 1987, his first tour victory in more than three years, he donated his entire $US108,000 cheque to Florida Hospital (now AdventHealth Orlando).

His love of family really came out the day of my visit. Daughter Chelsea was gone that day, but Aaron was around, and Stewart called him over, made small talk and tousled his hair. Stewart told him to look me in the eye when he shook my hand. Tracey was there, too, but she was mostly out of sight. Vin Scully, the great Dodgers announcer who for years also did golf telecasts, told me the one golf image that affected him most was Stewart stopping alongside the 12th hole during tournament play to dash over and give Chelsea a hug. Payne spoke a lot about his father, Bill Stewart, a fine player himself who dressed brashly and played in the 1955 US Open. When Payne entered a USGA event, his dad insisted he write his full name – William Payne Stewart – on the entry form. Payne, by the way, went by “Bill” when he played in the 1974 US Junior Amateur. He spoke fondly of his two older sisters, Lora and Susan, who roughhoused with him when he was young to toughen him up. Payne could cook, sew and iron, but he was no pretty boy. He was a vicious competitor and was notorious at sporting events for the abuse he hurled at coaches and players. He also spoke of his mother, Bee, and told of the alcohol intervention the family had done with her years earlier. After Payne passed, she at age 81 ran for the Missouri House of Representatives.

Stewart in 1999 was very open about his small addictions –he liked his cocktails (“two or three or four martinis”), not to where it was a serious problem but didn’t leave him feeling good. Socially he loved cigars, the occasional cigarette and Skoal chewing tobacco. He was talking about how he was off and on with all of it but was in the process of quitting. Moments later he spied the round outline of a tobacco tin in my front pocket. He looked around like a kid about to swipe a candy bar and whispered, “Break it out.” He loaded up, sighed with pleasure and then said, “We need to quit this s–t.”

Stewart that day was critical of the PGA Tour about the same issues players complain about today. He wanted bigger purses and more money for players who made the cut. He wondered aloud about transparency, finances in general and tour officials’ private jets in particular. That was 25 years ago. If Stewart were alive, would he have gone to LIV? There’s a theory that guys who cry during the national anthem don’t go to LIV, and Stewart was a patriot who welled up every time. So, no, but there’s little doubt that commissioner Jay Monahan would be getting some tough love.

He talked of his moodiness, brought on by streaks of underachievement and his ongoing battle with ADD, which wasn’t diagnosed until 1995. Stewart possessed great charm but also could be snappish and cutting. Starting in 1985, when I’d hit him up for instruction tips and golf conversation, he was a blast. He’d finished third in the 1984 National Long Drive – his swing masked remarkable power – and Golf Digest presented the event, so he was deferential. Then he entered a three-years-plus period in which he won twice but lost five tournaments in playoffs. Writers dubbed him “Avis” after the car-rental company, which touted its second-place status in the industry in an ad campaign, which irritated him to no end. “You writers have the pen, and you buy your ink by the gallon,” he groused. Another lousy streak from mid-1991 to ’99, brought on by an equipment change, made him even less fun to be around – but he got better.

The ADD made him hard to play with. One former PGA Tour caddie told me of the time Stewart was jingling change in his pocket while his player was preparing to putt. He knew Stewart, knew the jingling was only an absent-minded ADD thing and walked over to him and said, “Payne, how old are you?” Stewart answered, “Thirty-four. Why?” The caddie said, “A little old to be jingling change, right?” Stewart was embarrassed and apologised. He was a great sportsman, and film exists of him charging into the gallery at the 1999 Ryder Cup to demand that fans who were abusing Colin Montgomerie be ejected. He conceded a putt to Montgomerie on the last hole that day – a putt that gave Monty the win, not a tie.

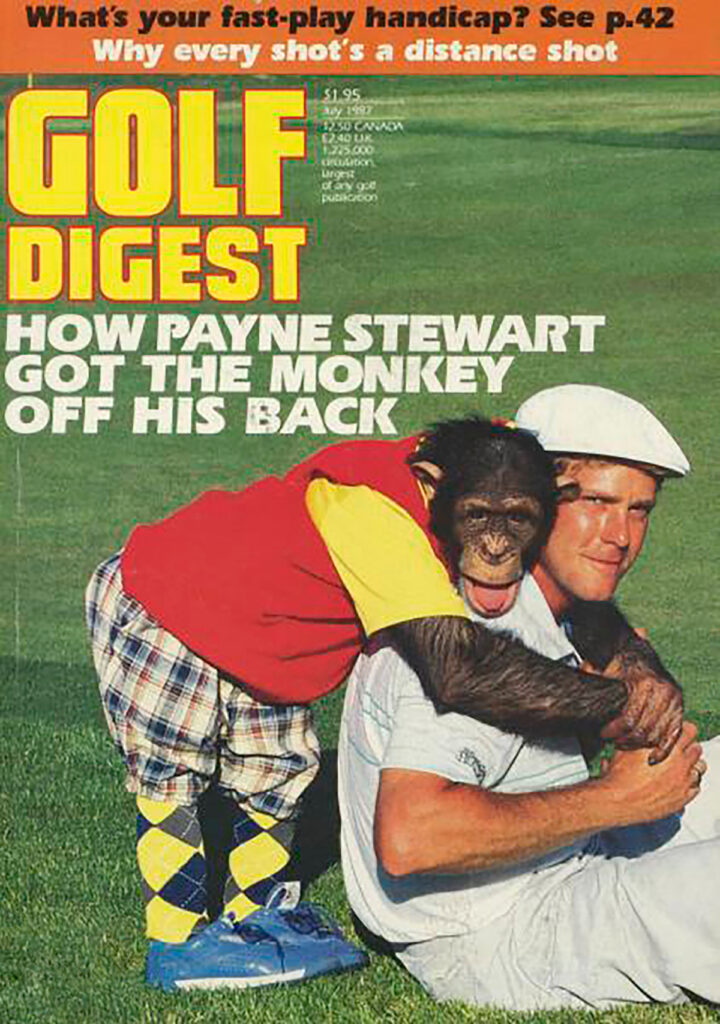

After his victory at Bay Hill in 1987, he posed on a US Golf Digest cover with a chimpanzee named Deena hugging him from behind. “How Payne Stewart Got the Monkey Off His Back” was a bestseller and his mother’s favourite image of him. The chimp took a curious liking to Stewart. Our photographer, Steve Szurlej, remembers delivering the chimp and her trainer to the shoot and Deena fooling with the car keys in the ignition and gearstick while the car was running. One of the first things Stewart asked during my 1999 visit was, “How’s Deena doing?” I told him I had no idea. Stewart had a long memory.

Stewart’s legend wouldn’t be near what it is without him being a superb player. Johnny Miller envied Stewart’s medium-high ball flight, Arnold Palmer pined for Stewart’s rhythm and Lee Trevino, who felt that every great player had at least one weakness somewhere through the bag, made an exception for Stewart. “That kid has the whole package,” he said. To stand near Stewart on the range and watch him hit balls – to hear him hit balls because the sound of impact seemed louder than most players – was a treat.

He was at his best playing hard courses, and he relished bad weather, two marks of a great player. Watching the replay of him that misty Sunday at Pinehurst in 1999, when he scissored the arms off his rain jacket to give him more freedom, reminded me of a 1989 quasi-instruction cover piece I ghosted for Stewart. It was titled “Cold, Wind and Rain”. He said that as a kid he played even when it snowed and spoke of the golf ball growing as it collected snow on the greens. He talked about dressing in layers, an obvious photo op. I assumed the first layer would be a pair of Spandex long johns, but Stewart emerged from the changing room wearing only briefs. “Absolutely no way we’re shooting that,” I said. “But it’s the first layer,” Stewart protested. An endearing thing about him was his utter lack of self-consciousness, be it apparel, speech or his unabashed harmonica playing.

Aaron, now 35, graduated from Southern Methodist University and captained the golf team. He became a marketing executive for Hilton Grand Vacations and tournament director of its namesake event on the LPGA Tour. He married and became the father of two children. Chelsea, 38, also married and is the mother of two. It’s a fun irony that one of Bill Stewart’s last bits of advice to son Payne was, “Only have two children.” Payne and Tracey did it that way and so have their kids – so far, anyway. Tracey never remarried but, with Chelsea and Aaron, appears for the annual presentation of the Payne Stewart Award presented by the PGA Tour.

In a beautiful documentary on Stewart titled “Payne”, Tracey Stewart said that years before the plane crash, Payne bought her mother a beautiful wristwatch. Both of her parents were staying with the Stewarts on the morning of the accident and were visiting Epcot Center when the awful news arrived. “That morning at 9:30, her watch stopped,” she said. “It was 9:30 when they would have perished.”

Everything stopped that morning for so many people, but it’s amazing how time eases heartbreak so that it isn’t the chief thing that filters through. Stewart’s victory celebration at Pinehurst – and that snippet of the wild character running into the street at Bay Hill – just makes me smile.

The Latest News

-

December 26, 2024Cricket: Australia’s Kostas gets better of India on debut

-

December 26, 2024Sam Konstas in epic response to MCG heroics amid wild Jasprit Bumrah detail

-

December 26, 2024Konstas, Kohli mid-pitch shoulder bump under microscope | cricket.com.au

-

December 26, 2024‘Clown behaviour’: Kohli blasted for ‘pathetic’ exchange

-

December 26, 2024Sports News Today Live Updates on December 26, 2024: India vs Australia BGT 2024-25: Sam Konstas shocks India with his remarkable debut | Watch