Inside the speed lab where pros go to power-boost their golf swings – Australian Golf Digest

- by Admin

- October 27, 2024

Almost an hour outside of the thriving metropolis of Dallas, Texas is a place called Denton, a small town with a snug array of shops and restaurants, which are lorded over by the brown, boxy dormitory tower of Texas Women’s University.

Every day TWU students flow through this small Texas town, and most days are the same. Except every so often, when if you look closely, you may spot one of the best golfers on the planet walking through.

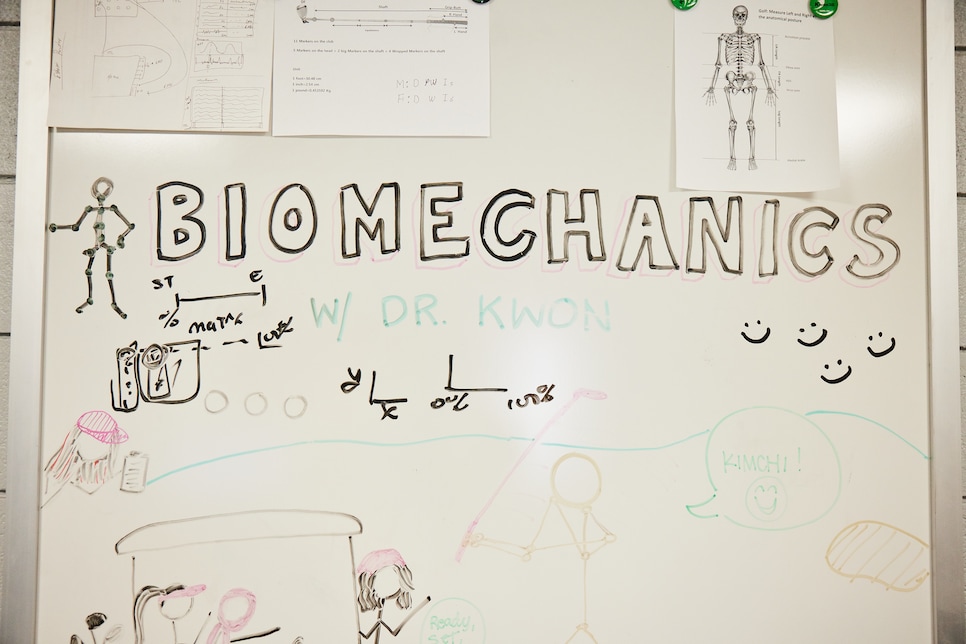

It’s a quest for distance that draws these players to Denton, because hiding here in plain sight is one of the most advanced golf biomechanics laboratories on the planet, led by one of the smartest men in golf today: Professor Dr. Young-Hoo Kwon.

It’s here where Dr. Kwon uses sensors to track hundreds of thousands of data points for the key joints in golfers’ bodies. It pairs that with how the golfer twists and turns against the ground, along with the club, itself. Put them all together, and it provides a complete picture of how a golfer swings the club. How their golf swing generates power—and the flaws which may cause that power to leak out.

An outsider’s entrance prompted only a momentary pause from the five students scuttling around inside. One of the students, a tall, young man named Hunter Alvis, walked over. Hunter is a PHD candidate who came to study under Dr. Kwon. His dream is to work for NASA, and he’s already co-created three biomechanics-related patents to protect astronauts from the strain of space travel.

“Dr. Kwon is in his office, but you can get warmed up right here,” Hunter says in a clear, clipped tone. He points to a simulator off to the side.

“Is this your driver?” he asks as he slips off its headcover and pulls it from my golf bag. “I’ll be needing that.”

***

For as long as there have been golf balls to hit, golfers have wondered how best to swing at them.

In the before times, golfers gleaned whatever information they could by analyzing their divots, and relying on the movements they could spot in their own shadows. Video cameras began to take hold in the 80s and 90s, which helped golfers grapple with the basic geometry of their own golf swings. Ball-tracking technologies, like Trackman and Foresight, came along in the early 2000s. A huge landscape shift which allowed golfers to measure exactly what the golf ball was doing, and deduce what was causing it.

Now, golf swings are in the era of 3D. Advanced systems that allow golfers to measure the most minute movements of their own body as they swing. Your naked eye may not notice that your right arm is moving in a way that’s costing you power, but a 3D system will pinpoint it instantly. It’ll tell you how many degrees your right arm is rotating; how many millimeters it’s bending; how fast it’s moving; when the problematic action starts, and how it compares to others.

If video cameras are X-Rays, 3D systems are golf’s equivalent to MRIs.

In 1991, then a doctoral student at Penn State University, Dr. Kwon built his own MRI machine. He’s been on the forefront of the technology ever since.

Dr. Kwon started as an astronomy student, but gravitated toward golf after discovering what he describes as a natural talent in recognizing good motion patterns. With astronomy providing a foundation in mechanics and programming, he began coding his program, Kwon3D, into existence. It started initially as a general-purpose system for all sports, but as more golfers began rolling through, Dr. Kwon found the mysteries and complexities of the golf swing too alluring to ignore. Just as some catch the golf bug after a heroic shot on the course, Dr. Kwon caught his in a lab.

“The golf swing has so many mechanical components,” he says. “Once I started studying it, I fell in love with it.”

By 2007, Dr. Kwon started building golf-specific features into the program. He began publishing his findings in academic journals across the world, on subjects ranging from the “motion planes of the ‘functional double-pendulum’” to analyses of how the golf swing breaks down under extreme stress conditions.

In 2013, he launched a golf swing analysis service, and began a certification process to help coaches apply his learnings.

Dr. Kwon calls these reprogramming sessions, and golfers of all sorts fly across the world to get them. He’s reprogrammed more than 300 golfers’ swings over the years, from weekend warriors to promising juniors; long drive champions like Jamie Sadlowski and Eddie Fernandes; PGA Tour veterans like Matt Kuchar, and Charles Howell III; to major champions such as Hideki Matsuyama, Bryson DeChambeau, Vijay Singh, YE Yang, and Trevor Immelmann.

The goal for each is the same: Squeezing more yards out of their golf swing, in a distance-crazed era of the game.

“We recently did a study on junior golfers. They gained an average of three percent clubhead speed after just 45 minutes,” Dr. Kwon says. “It’s usually more. Even for tour players, you’d be surprised. By obeying certain mechanical principles, Golfers can swing the club much faster than they think they can.”

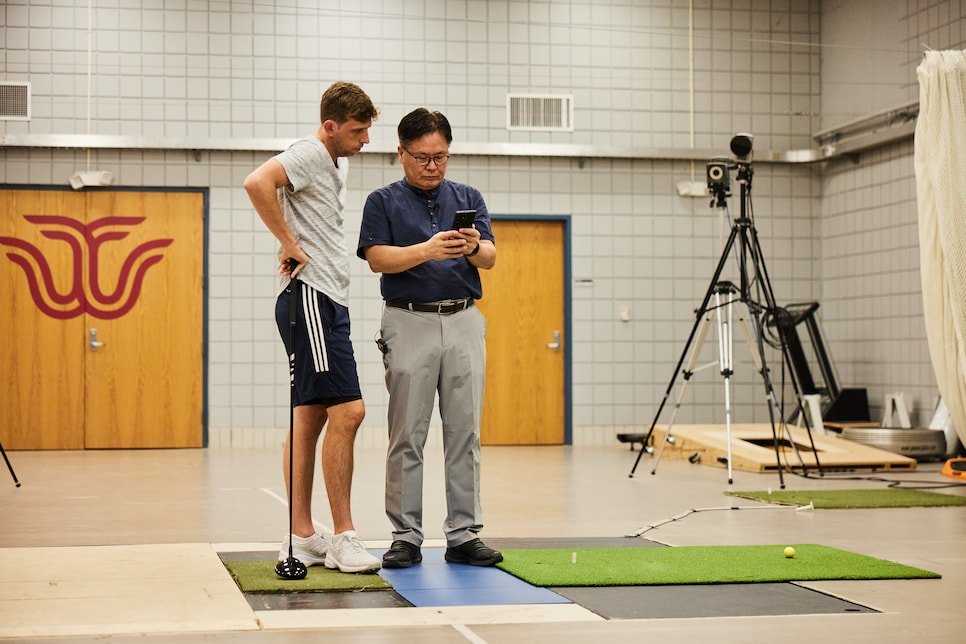

Dr. Kwon, a stocky man with glasses and a friendly face, enters with a big smile. He walks over to the bay where I’m hitting balls, peering over the shoulders to inspect his graduate students’ work along the way.

“Welcome,” he says, shaking my hand. “First, warm up. Then you can get changed and we can begin.”

Dr. Kwon’s system relies on a network of more than 10 cameras stationed 360 degrees around the golfer. To gather the data, the subject is covered in more than 30 reflective dots the size of a small pearl, the same way an actor undergoing a CGI transformation for a movie would. Each camera tracks the movement of each of those dots at a rate of more than 1,000 frames per second.

In order to apply those reflective dots without any interference, though, golfers need to strip down to nothing more than golf shoes and a single pair of spandex shorts. The price of getting re-programmed. I sheepishly ask if I can wear a sleeveless spandex shirt I brought in a last-minute attempt to protect my fragile male ego.

“We really prefer shirtless,” Hunter says. “It’s much more accurate that way.”

Once I re-emerge, I walk past one of the graduate students carefully moving a reflective, T-shaped wand up and down, over his head and then back towards the ground. It looks like a kind of slow motion dance ritual that they call the “wand dance.” It’s a process that sets the space where I’ll soon be swinging, so the computer knows where to look.

My driver that was whisked away earlier is now covered in transparent reflective dots, and the three remaining graduate students descend to do the same to me. I feel awkward, but I quickly realize I’m the only one who does. To everyone else in the room, I’m just another guinea pig.

It’s one of the best things about golf. That it’s a game which forces you to confront your own ego in a quest for improvement. How far are you willing to go, to get a little better?

I think about this as I adjust my spandex shorts, walk over to the hitting bay, rear back and take my first swing.

***

“Alright,” Dr. Kwon clears his breath and adjusts his glasses. “This is your report.”

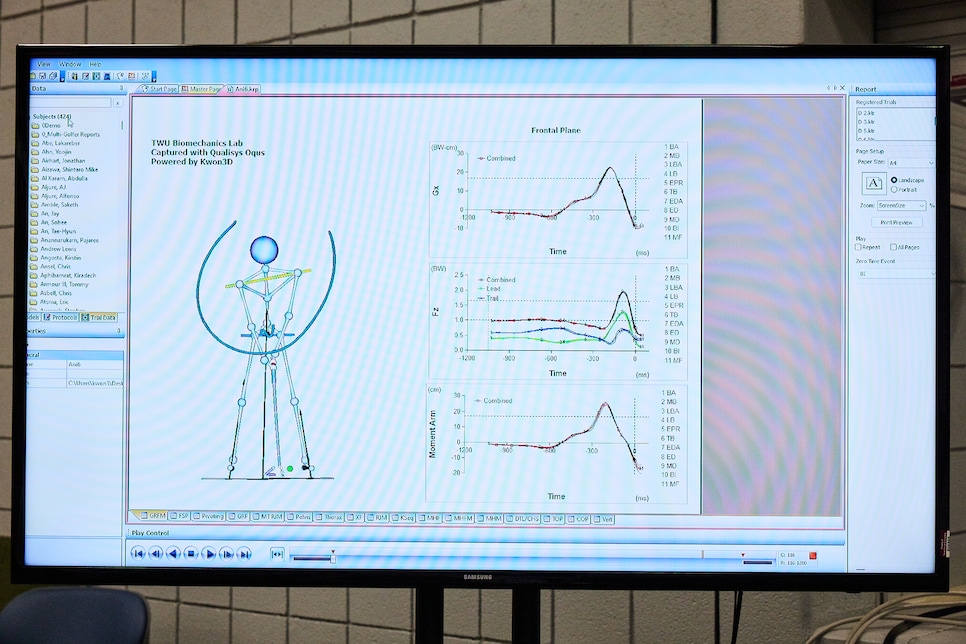

Dr. Kwon points to a television screen in front of me, displaying a stick figure golfer that’s surrounded by circles and lines and graphs and arrows and other squiggles. Dr. Kwon is at the controls, sitting next to me and using a mouse to click through the 10 different tabs of data he just collected from my swing. The process was surprisingly easy: 15 drives into a net just as you would down an unthreatening fairway, and now comes the doctor’s diagnosis.

The golf swing, in the simplest terms, works like a wheel on an axle. The club and arms, in this analogy, are the wheel, and the body is the axle. The powerful hub that rotates the wheel. The more efficiently you move your body, Dr. Kwon explains, the faster your club and arms can turn through.

“We need to generate the best possible rotation in the body, and with that we generate the high clubhead speed,” Dr. Kwon explains. “We need to accelerate the rotational motion. And in order to accelerate, we need to torque the body.”

There are lots of ways to swing a golf club, but as Dr. Kwon makes his way through my golf swing MRI, it becomes clear that there are a few hills that he will die on. These signify the biggest power leaks in the golf swing, and you can spot them on every driving range or country club in America—whether you realize it or not.

The myth of ‘low and slow’

Almost immediately Dr. Kwon makes clear that he wants golfers to make a fast backswing. He calls it an “active” backswing. To rip the club away from the ball as fast and hard as they can.

It defies one of golf’s oldest pieces of homespun wisdom, one peddled by the likes of Ben Hogan and Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods, and everyone in between: That golfers should take the club away low, and slow.

The problem is that while many top golfers are quick to dispense that piece of advice, it’s not what they actually do. A cursory look at Ben Hogan’s swing shows how he used to whip the club away, and as Dr. Kwon began studying his own data, he found pros often move the club from zero to upwards of 15 mph during the first few feet of their swings. Amateurs, by contrast, rarely move it faster than 7 mph.

The problem with slow backswings, specifically, is that they don’t require much effort, so golfers get lazy. Moving the club away forcefully requires golfers to engage the muscles in their legs, shoulders, core, and arms to create a powerful turn. The slower the backswing gets, the more golfers lift the club weakly into position, and often take a strange, inefficient route to get there.

“With the slow backswing you can introduce all sorts of problems, by simply making the backswing fast, we can eliminate a lot of them.” Dr. Kwon says. “In a sense you cannot go too fast.”

Don’t pause

Dr. Kwon seems well-drilled in navigating golfers’ fragile ego, because as he moves through the tabs and graphs, he starts by pointing out the stuff he likes. He seems satisfied by the speed of my backswing, which I hadn’t thought much about but am relieved nonetheless, along with the short backswing pause at the top of my swing.

Like slow backswings, long backswing pauses are the death of good golf swings in Dr. Kwon’s eyes. From the start of the swing to impact, Dr. Kwon wants the swing to take no longer than one second, he says, and the pause at the top of the swing no longer than 0.22 seconds.

That’s because when golfers make a backswing, they’re not just turning, they’re stretching up towards the sky. This stretch has the same effect as if you were to jump, if only for a millisecond. It initiates a process coaches call “unweighting”; golfers get light on their feet as their muscles stretch and then shorten and golfers begin plummeting back to earth. Like winding up before thriving a pitch, it slingshots the club to faster speeds.

An elongated, intentional, manufactured pause at the top of the swing disrupts this “flow,” as Dr. Kwon calls it.

“When you have an active backswing, it connects the backswing to the downswing,” Dr. Kwon says. “If you have a long pause, you just lose the effect of the backswing, so you have to start all over again before the club begins.”

This was the topic when Hideki Matsuyama visited the lab in late 2019.

“I explained the issues with it, and obviously advised him against it,” Dr. Kwon said.

Whatever he advised, it got through. Matsuyama began shortening his transition, and underwent speed training sessions with his driver that would force him to move quicker back and through.

“I really don’t know how that pause got into my swing. I do know that the pause has gotten a lot shorter” Matsuyama said at the time. “Now, I imagine a flow that cuts back and through.”

By 2021, Matsuyama had shaved a precious few seconds off his pause, and that spring, slipped on his first green jacket.

Step your way to success

Step your way to success

About halfway through the analysis portion of the session, I can see Dr. Kwon begin to hint at some of the problem areas in my swing.

If there is one central, common denominator in Dr. Kwon’s approach is that the body should drive the swing, not the arms. Yet golfers fall into the trap of arm-driven swings all the time. When the arms move too soon, the club flies over-the-top, and can cause slices. When the wrists fire out of order, golfers begin scooping and chicken winging, causing contact issues.

Having an arm-powered golf swing is like having a wheel-powered car: It’s an idea that doesn’t make sense.

The problem with arm-driven swings isn’t the arms, though, but the body. If your golf swing is arm-driven, in Dr. Kwon’s mind, it’s because the body isn’t being active enough. That’s what fast backswings and short pauses do. They get the body — the engine of the golf swing — moving.

Dr. Kwon points to the screen, at a red dot hovering in the middle of my stick figure golfer’s body. That red dot represents the center of mass of my body, which for most humans is located just below your belly button. As my stick figure golfer moves through the swing, the dot oscillates subtly side to side.

“It doesn’t move much,” Dr. Kwon says. “We need more lateral movement back and forth.”

Moving your body’s weight back and forth propels the arms back and forth by creating what’s known in physics as a moment arm. Just as a long wrench makes a bolt easier to turn, a bigger weight shift creates a longer moment arm, which is why the more golfers shift their weight from foot to foot the further they’ll hit the ball.

It’s a move that pros, more than anything else, are a lot better at than the rest of us: pros shift their body about two inches away from the target on the takeaway, then move it all the way back to more than five inches towards the target. Most amateur golfers don’t do the second part. They’re lucky if they get back to zero. It causes over the top moves and casting and chunks and skulls and everything in between.

The solution Dr. Kwon arrives at, though, is fairly simple: Literally kick-starting their golf swing with a trigger move.

“Lifting their right foot off the ground before they take the club away, or moving their right knee towards their left. Something that moves your pelvis from side-to-side without moving your head,” he explains. “You don’t need a lot, but once you add a little lateral motion, the stepping motion really helps the swing.”

“I’m a big fan of the stepping motion,” Padraig Harrington, who has studied Dr. Kwon’s work, adds. “I’ve played entire tournaments stepping, and it’s something that would help loads of golfers.”

Find the downswing “expressway”

The relative lack of side-to-side motion is an issue, but the biggest problem in my golf swing is about to reveal itself.

“Do you see this?” Dr. Kwon leans back and grins. He knows what’s coming. “Do you notice the shape?”

Dr. Kwon is referring to a semi-circle which spans the bottom half of my golf swing. Except, there’s something off about it. It looks more like a “V” than a “U”, and a crooked one, too. The bottom of the arc is more towards my right leg, and the left side of the “V” is higher than the left.

This shape indicates one of the most common power leaks in the golf swing, and one that plagues the ranks of amateur golfers.

The U-V shape is created by tracking the path of the hands as they move through the golf swing. It should look like a perfect U. Mine looks like a right-tilted “V” because my arms get stuck behind my body on the downswing, which causes me to save them by shoveling them out to the right and flipping.

“This is actually the worst motion for power,” Dr. Kwon explains. “This means essentially your body is obstructing your arms.”

The opposite of this problem is a left-tilted V, which Dr. Kwon calls a “spiral swing” because of how it makes the golf swing look from a different angle. That’s the classic over-the-top move; whereas my body obstructs my arms before they get to the ball, these arm-driven swings see golfers’ body obstruct their arms on the other side of the ball. It prevents a full release of the club, and many times a “chicken wing” release.

“We want our arms to find the expressway,” he says. “When your right elbow clears the body on the downswing and you can let the club go down the line.”

Dr. Kwon leaves the room and returns a few moments later with a one-inch thick, seven-feet long, wool rope. That’s his go-to drill for golfers who struggle with this, because golfers with an asymmetrical swing won’t be able to swing a rope continuously back and forth.

At first that’s what was happening to me. I’d take a backswing, feel the rope touch below my left shoulder blade, then swing through and feel the rope hit me near the face.

“Throw it awayyyy,” Dr. Kwon says, demonstrating. “Then let it goooo.”

A few minutes later I’m swinging the rope back and forth, as hard as I can. I can feel the rope hitting me evenly on each side of the ball. My arms are flying down the golf swing expressway. Dr. Kwon was calm before, but he’s animated now. Every few swings he’ll stop me and excitedly show me videos of my new swing, then switch the rope for the driver and repeat. When it’s time for me to leave, his parting words are simple.”Trust the rope,” he says.For as much cutting-edge technology as Dr. Kwon peddles in to uncover the flaws in my swing, there’s something delightfully old school about the solutions he uses to fix it.

***

I’ve played a lot of golf in my life, and hit many thousands of golf balls. But I can’t remember the last time I was so sore from making golf swings.

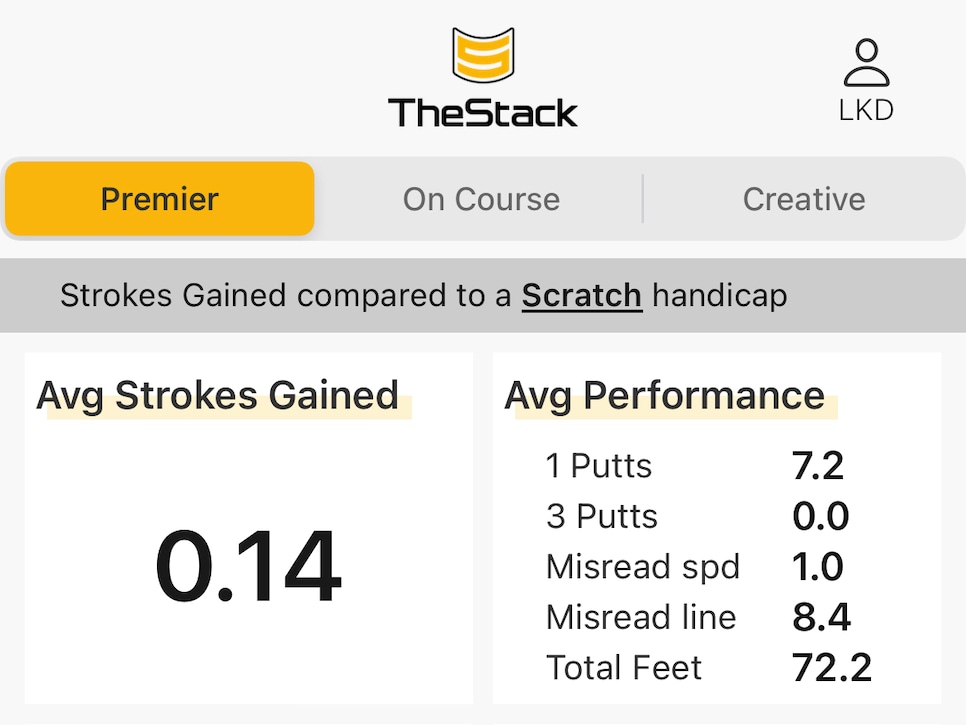

Before I left to see Dr. Kwon in Texas, my ball speeds were hovering around 154 mph — about enough for a 270 yard average. But I’m back in front of a simulator now, a week later, and I hit another drive into the screen in front of me. 159 mph is the number that pops back.

That’s become the new norm. A faster takeaway leading to a shorter backswing pause; a stepping trigger to start my swing when I need a little extra; and lots of rope swings. That unusual combination unlocked a quick five mph boost to my drives. A boost like that would be enough to propel a PGA Tour player with an average ball speed to within the top third on tour. That’s enough for a few hundred thousand dollars. Maybe even a win. A few extra miles per hour, but a career made.

The stakes are lower here, but like every golfer, I’ve still got buddies I want to beat. So I pick up my rope, and make a few more swings.

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com

The Latest News

-

November 15, 2024Australian tech leaders demand reform of government ICT spending

-

November 15, 2024Competing for 28th time this season, Alexa Pano is learning some tour lessons the hard way – Australian Golf Digest

-

November 15, 2024I talked batting with Bradman in 2000. What he told me explains Test cricket’s decline today

-

November 15, 2024Mike Tyson vs Jake Paul LIVE: Aussie shows ‘incredible guts’ in loss; brutal wake-up call for Tyson

-

November 15, 2024Afghanistan women’s team green-lit for ‘dream’ clash