Cricket’s commentator crisis: Endless wave of ex-players is not what everyone wants to hear

- by Admin

- November 7, 2024

The jacaranda trees are in flower, summer has arrived, Christmas is coming, and so too another cricket season – the Indian team are here for five Test matches. For as long as I can remember, I have loved Test cricket. I have early memories of huddling around the wireless in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) listening to matches in England and Australia. For some strange reason, my favourite cricketer was the Australian batter Neil Harvey; possibly because I had some early pretentions as a left-handed batsman. There was a sense of magic in the evolving drama coming live via the BBC through the voices of John Arlott, Alan McGilvray, EW Swanton, Norman Yardley, Charles Fortune and others.

The Test matches from the Australian tour of England in 1961 and the South African tour of Australia in 1963/4 are vivid in my memory, no doubt reinforced by much reading over the years. My first ‘live’ attendance at a Test match was in Durban in December, 1964, when South Africa played England at Kingsmead. The ground had one pavilion, with most spectators filling the grass banks around the ground in deck chairs. Prior to the game and during lunch and afternoon tea, we children hurdled over the boundary fences and played multiple little ‘Test’ matches with a bat and tennis ball.

Some of the older folk stood around the roped-off wicket and pontificated over the state of the pitch and whether the incoming tide would bring a rush of wickets – a long-held myth in Durban. There were no announcements over loud speakers, and no one moved during an over so as not to upset the view of other spectators. Maiden overs, fifties, centuries, boundaries, partnerships etc. came and went and were all given suitable applause at the correct moment as most in the crowd were actually closely following the game. Some fans, myself included, recorded each ball in our own, often homemade, scoresheets. There were three Rhodesians in that South African team: Tony Pithey, that prince of fielding, Colin Bland, and the bespectacled Joe Partridge who had such a successful tour of Australia in 1963/4, taking 25 wickets in the five Test matches.

David Warner is the latest former player to step into the commentary booth. (Photo by Jason McCawley – CA/Cricket Australia via Getty Images)

I watch Test cricket now on television. I occasionally listen to it on the radio. Although I find the noisy jingle and associated hype tedious, the magic of Test cricket is still there to be found. Like a chess game, it evolves over the overs, hours and days; there were many wonderful moments during this recent Ashes series. I am afraid that the shorter versions of the game hold very little attraction for me. There is ‘sameness’ about it all. For me, Test cricket is a bit like a bottle of appropriately chilled Dom Pérignon, and the shorter version, a diet Coke. For the T20 game, the diet Coke is warm. No doubt many will disagree. I have no problem with that. Cricket lovers are a catholic lot.

My particular sadness nowadays is the paucity of good commentators – radio and television – and journalists. We have a surplus of people, many former cricketers of note, who have little idea of effective communication in these media. Much of the commentary is banal. We are bombarded by graphs, statistics, constant references to the former deeds of the commentators, and an over-analysis of slow-motion images that are now afforded to us through extraordinary technology.

A long time ago I read something from Richie Benaud reflecting that a successful captain must have a measure of ‘luck’. Not many graphs around on ‘luck’! (Benaud was a rare person who understood that in television commentary you merely complemented the visual; he only spoke when it was necessary; his silences were powerful).

Richie Benaud. (Photo by Ryan Pierse/Getty Images)

Graphs and statistics also rarely take into account context. Most grounds now have smaller boundaries, bats are bigger and lighter, wickets are covered and better prepared – one could go on and on. And, recently, we have been subjected to a dismal deluge of backbiting, personal slights and the airing of perceived long-held grievances between current and former players – rather pitiful public chatter. No doubt it will generate ‘interest’ on social media forums (often the most important ‘key performance indicator’ for some media outlets), but really, and this will sound pompous, it is not cricket.

To illustrate my particular sadness over this state of affairs, let me share a few things from our collective cricket canon – because it is ‘our’ canon. We just need to revisit it sometimes to see what riches there have been and are possible.

My favourite cricket writer is Neville Cardus, who for many years was the cricket and music critic for the Manchester Guardian. Cardus in his autobiography wrote this of his own wedding:

“I married the good companion who is my wife during a Lancashire innings. The event occurred in June, 1921; I went as usual to Old Trafford, stayed for a while and saw Hallows and Makepeace come forth to bat. As usual, they opened with care. Then I had to leave, had to take a taxi to Manchester, there to be joined in wedlock in a registry office. Then I – that is, we – returned to Old Trafford. While I had been away from the match and committed the most responsible and irrevocable act in a mortal man’s life, Lancashire had increased their total by exactly 17 – Makepeace five, Hallows 11, and one leg-bye.”

Who but Cardus could describe 1924 Trent Bridge in Nottingham “as a lotus land for batsmen, a place where it was always afternoon and 360 for two wickets”? Later in 1938, on the eve of the first Ashes Test he wrote, “time does not invade Trent Bridge with irrelevant modernity. New stands and increased comfort fall into place”. The scorecard for this Test reflects that nothing much has changed since 1924 in the ‘lotus land’: Charlie Barnett 126, Len Hutton 100, Eddie Paynter 216* and Denis Compton 102, scored centuries for England; Don Bradman 232, for Australia.

Don Bradman. (Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

Another favourite was John Arlott – journalist, commentator, wine connoisseur and poet (he also wrote the occasional hymn). Following an early career with the Southampton County Borough Police Force, his journalistic career began in 1950 with the Evening News and the Daily Mail. His literary skills with his distinctive voice combined to make him one of the great commentators of cricket. For those who have not heard, a visit to the internet will allow you to hear his poetic phraseology.

Here’s something from Arlott during England’s 1948/9 tour of South Africa when the England captain, George Mann, was bowled by the South African spinner, Tufty Mann, with Arlott describing it “as a case of Mann’s inhumanity to Mann”. Years later when a streaker entered the field of play, Arlott reflected: “We’ve a streaker down the wicket now, not very shapely and it’s masculine. And I would think that it’s seen the last of its cricket for the day… He’s being embraced by a blonde policeman and this may be his last public appearance, but what a splendid one”.

Here is Arlott writing on a few cricketers:

On Mike Brearley, the then English captain: “He has a strikingly open mind; but a firm set of standards. Much of his strength as a captain lies in the fact that cricket is not the be-all and end-all of life for him. … One is reminded of CLR James’ text in that fine book ‘Beyond the Boundary’: “What do they know of cricket who only know cricket?” (A friend of mine who lives in Geneva recently commented that he remembered Arlott on the radio hinting that he thought that Brearley was the best British leader since the Duke of Wellington!)

On Colin Milburn, the England opener: “There he stood, vastly rotund, apparently – though not actually – relaxed; left toe cocked in the manner of W.G. Grace; and unmoving. When the ball came, if he liked it – and he had a wide range of acceptance –he hit it.”

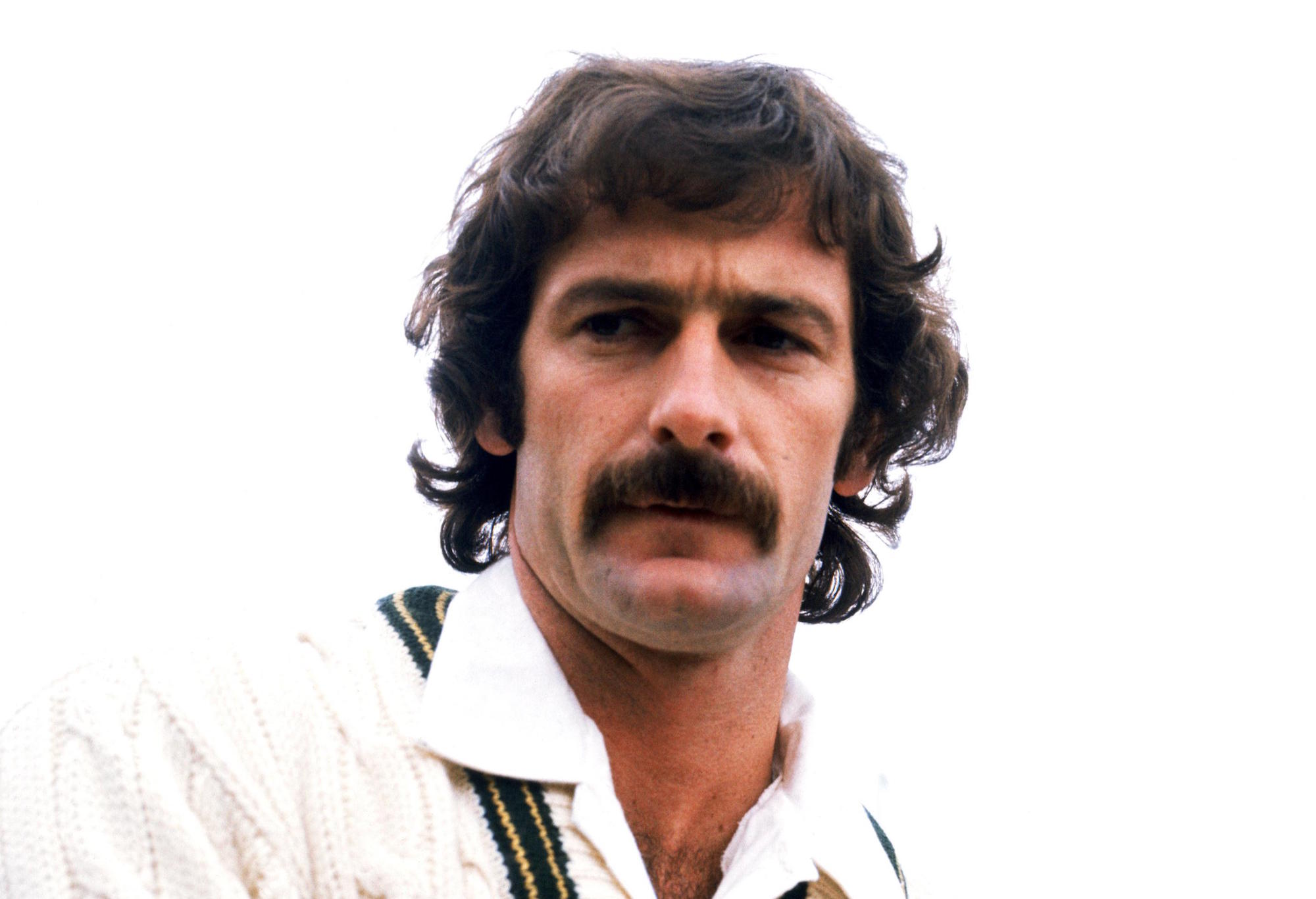

On Dennis Lillee, the Australian fast bowler: “A superb fast bowler with a classical flowing action, and a fundamental hatred of batsmen. … He was fortunate that his judges were a laughingly pusillanimous and Packer-fearful Australian Board of Control.”

Dennis Lillee. (Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

On Clive Lloyd, the West Indian captain: “… is virtually irreplaceable; reliable, loyal, match-winner; glorious entertainer; thoughtful, humorous, modest and courteous man; they shall miss him both on the field and off it. Meanwhile, they, and all of the cricket world, should relish him while he is still there.”

I have just given a few examples from two of the greats from the past; there are many more. There are even a few around today. I could go on, but we only have five days and a draw, contrary to what some people said in the recent Ashes series, is an honourable result and very much part of the game.

But what would I know? EV Lucas back in 1897 wrote: “I am again perplexed by the passion for this game which is displayed by those who cannot shine at it. They cannot bat, they cannot bowl, they leave their places in the field, they miss catches, they fumble returns; and yet, every Saturday, there they are, often in perfect flannels, ready to fail once more. What is this lure, this attraction, that cricket exercises, and why is it that so few village elevens can ever muster more than two or three players who know anything?”

That could be me. I suspect that CLR James was correct in thinking that those who have wider and varied interests outside of cricket, may be the best to write and commentate on this game so many love.

The Latest News

-

November 7, 2024‘Sand Valley on steroids’: Bandon’s founders discuss why they’re excited about their new project in Florida – Australian Golf Digest

-

November 7, 2024Sports Illustrated shares first photos from Nelly Korda’s 2025 SI Swimsuit shoot – Australian Golf Digest

-

November 7, 2024Where to watch Australia vs. Pakistan 2nd ODI: Free live stream, free-to-air channel, start time for cricket match | Sporting News Australia

-

November 7, 2024Cricket’s commentator crisis: Endless wave of ex-players is not what everyone wants to hear

-

November 7, 2024Australia plans