More US McDonald’s customers fall sick with E. coli — could the same thing happen in Australia?

- by Admin

- October 28, 2024

A growing outbreak of E. coli linked to McDonald’s hamburgers sold in the United States has landed the multinational in court, and a food safety expert has since weighed in on the possibility of a similar incident happening in Australia.

One American customer has died from the bacterial infection, 22 others hospitalised and 52 more cases identified, which spans 13 states across the US’ west and mid-west regions.

McDonald’s officials said a California-based company which produces onions used in Quarter Pounder hamburgers could be to blame for the spread, and stores in 12 states have already removed the ingredient from their cooking processes.

The fast food chain’s Chief Supply Chain officer Cesar Pina on Sunday ruled out Quarter Pounder beef patties as the source of the infection, after the Colorado Department of Agriculture said all sub-samples from multiple lots of McDonald’s brand fresh and frozen beef patties had tested negative for E. coli.

The company said in a statement that slivered onions from a Taylor Farms facility in Colorado Springs were distributed to approximately 900 McDonald’s restaurants, including some in transport hubs like airports, and confirmed it has decided to stop sourcing the produce from the facility “indefinitely”.

Quarter Pounder burgers without slivered onions will be made available in all US restaurants in the coming week.

A spokesperson for McDonald’s Australia told the ABC there is currently no concern about food safety standards or the quality of hamburgers in any of its 1,044 stores.

Could an E. coli outbreak happen in Australian fast food stores?

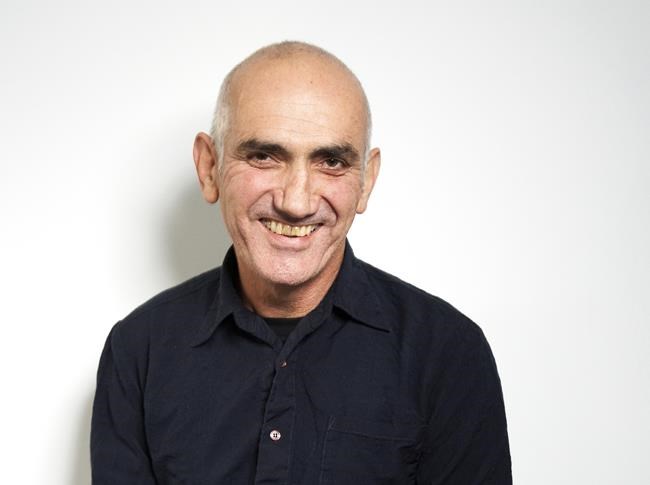

Gary Kennedy, the managing director of food safety consultancy group Correct Food Systems, said E. coli is typically spread to meat or other products through animal faeces or poor personal hygiene, but in Australia tight regulations govern the hospitality sector to prevent outbreaks.

“E. coli in raw meat is not uncommon, but it is an easy bug to kill and normal cooking will kill it off.

“Onions are also washed in a tumbling water bath like the flume ride in amusement parks, [they are] constantly being turned around like in a washing machine with 200 parts per million chlorine that not only washes them but the chlorine will kill microorganisms.

“You could cross-contaminate with dirty, unwashed hands… But the rules in Australia say you must wash your hands after you’ve been to the bathroom and when you enter a food premise.”

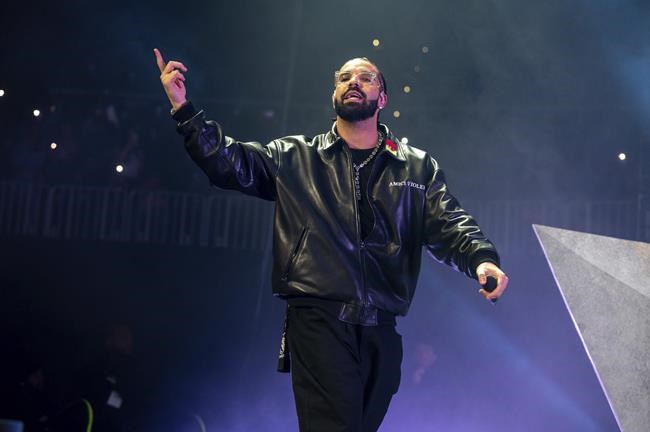

McDonald’s US has cut ties ‘indefinitely’ with the suppliers of its slivered onion products due to the ongoing E. coli infection outbreak. (Reuters: Andrew Kelly)

Mr Kennedy said those provisions make it unlikely for bacteria like E. coli to develop in produce eaten by Australian fast food consumers in Australia.

He also said a more dangerous strain of the bacteria is known to have spread in the US due to expectations from customers about how thoroughly food should be cooked, which differs from the views taken by Australians.

“In the United States they have an E. coli strain called O157, which is fairly common over there, and that does cause symptoms including kidney failure.

“Americans do like their meat to bleed a little and Australians really don’t. We like to our meat to be well-done when it comes to a hamburger and that’s to our advantage.

“We tend not to have the same dangerous strains in Australia as regularly.”

What are the food safety laws in Australia?

The federal government regulates the national hospitality sector with the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code and the Food Standards Australia New Zealand Act 1991.

The federal law says: “A food business must take all practicable measures to ensure it only accepts food that is protected from the likelihood of contamination,” and orders companies to “take all practicable measures to process only safe and suitable food”.

To prevent potential contamination Australian food providers are legally required to cool food from 60 degrees Celsius to 21C within two hours, from 21C to 5C within the next four hours, and to use a rapid re-heating process.

Australian food handlers also have to follow regulations requiring them to thoroughly wash their hands around ready-to-eat or raw food and after using the bathroom.

Punishments for breaching food safety laws vary in each state and territory, and range from fines extending in value into the hundreds of thousands up to potential jail sentences.

What would happen if there was an E. coli outbreak in Australia?

McDonald’s stores in the US have removed Quarter Pounder products, slivered onions or beef patties from their menus while federal public health investigations are underway.

McDonald’s said a California-based company which makes onions used in its hamburgers could be to blame for the spread of the infection. (AP: Charles Rex Arbogast)

Joe Erlinger, the president of McDonald’s USA, also released a video statement on October 22 to confirm E. coli had not been found in other beef products sold by the chain.

Mr Kennedy says if a similar outbreak was to occur in Australia, the immediate response among impacted businesses would be to follow suit and begin recalls of contaminated ingredients.

“Under law in Australia, the food service industry… Isn’t legally obliged to do recalls, however in a big brand name like a KFC or a McDonald’s, a Qantas, a Hilton, an organisation whose food service base has a high brand reputation, they don’t want to run the risk of other people getting ill or appearing non-responsive.

“A lot o these big chains, if there is a food poisoning outbreak, will be very up-front with the media to let them know what’s happening.

“In a restaurant chain or an airline or hotel chain, if there’s found to be a problem with an ingredient typically you’d throw it away, or if the supplier says ‘we’ll pick it up’, they’ll put it on hold, they’ll isolate it so it can’t be used.”

The Latest News

-

December 26, 2024Andy Roddick says he has one big concern about Iga Swiatek heading into the Australian Open

-

December 26, 2024Thanasi Kokkinakis injury: News, updates as Australian tennis player withdraws from Brisbane International | Sporting News Australia

-

December 26, 2024Trickle-down Konstanomics helps Aussie top-order fire | cricket.com.au

-

December 26, 2024Scottish psychotherapist urges debate on youth social media use after Australia’s ban – Scottish Business News

-

December 26, 2024Kohli to escape ban over shoulder clash with teen Konstas