The Man Behind Tiger’s First Deals – Australian Golf Digest

- by Admin

- April 24, 2024

Agent Hughes Norton breaks his silence with a new autobiography.

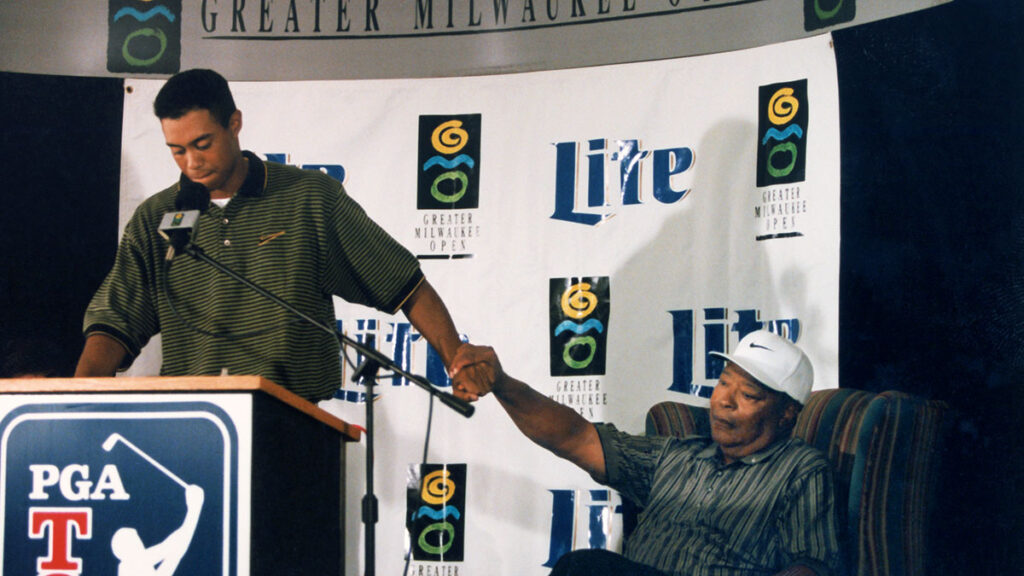

Editor’s note: It is no exaggeration to say that Hughes Norton operated at the epicentre of professional golf for nearly 20 years, helping legendary super-agent Mark McCormack grow the personal-management business McCormack created that at its height called the majority of the top 25 players in the world clients. While at IMG, Norton represented Greg Norman when the Australian world No.1 was at the peak of his powers and built a relationship with Earl Woods that resulted in the highest-profile new-professional-golfer-representation agreement of all time. Norton also led the negotiations that would make Tiger Woods the highest-earning active golfer on the planet before he hit his first shot for pay at the 1996 Greater Milwaukee Open. In this excerpt from his upcoming memoir, Rainmaker, Norton offers the first glimpse inside the negotiations and machinations that launched Woods’ branding juggernaut – with dollar signs attached that still stick out even in a world of LIV Golf mega-deals. – Matthew Rudy

I can’t recall the precise moment when I heard from Earl or Tiger that the decision had been made [to turn professional], but it was well before US Amateur No.3 because that week at Pumpkin Ridge Golf Club I had with me a couple of very big contracts for Tiger to sign, the fruit of several weeks of “what-if” negotiations with Nike and Titleist. By the time Tiger raised the trophy that Sunday evening in Portland, Oregon, his Nike logo apparel had been sized and tailored, his Nike shoes had been tested for comfort, and a Titleist staff bag emblazoned with his name and filled with a set of custom-fitted clubs was as ready to hit the PGA Tour as he was.

The process had begun two years earlier, just after Tiger won his first Amateur. (I was not officially his agent – I couldn’t be until the day he publicly renounced his amateur status – but we had a tacit understanding.) My strategy was a bit unorthodox – instead of stirring interest among several apparel and equipment companies in the hope of creating a bidding war, I decided to put all my eggs in two baskets – Nike and Titleist. It was a gamble, to be sure, but one I thought could pay off.

Nike, I suspected, would require more spadework than Titleist, so it was there that I commenced. Thanks once again to the unique resources of IMG, I had a couple of things going for me. A few years earlier our tennis division had established a strong relationship with Nike, bringing them the flamboyant Andre Agassi, who had been the perfect fit for Nike’s studiedly edgy image.

Nike’s director of sports marketing, Steve Miller, was the former athletic director at Kansas State University, where he had transformed a losing football team into a perennial bowl invitee by hiring Hall of Fame coach Bill Snyder. Steve would be my interlocutor in negotiating the Tiger deal.

After three or four visits with Miller, I felt my homework was completed, and I was ready to talk Tiger. Here was my thinking:

(1) The explosive growth of golf had not gone unnoticed by Nike. The company had made a tentative first move into the game with shoes and apparel and was on the cusp of a bigger commitment into clubs and balls.

(2) Nike prided itself on identifying with only the very best players in their respective sports – Andre Agassi, Michael Jordan, Jerry Rice. Stars drove the Nike brand.

(3) Those guys now were past their primes, aging out of the picture. Nike had not signed a megastar in years. They needed a win.

(4) Tiger would give it to them. The timing was perfect.

(5) Phil Knight was a jock sniffer who simply had to sign the best athletes. If he was already paying Agassi and Jim Courier big bucks, I reasoned, imagine what he might pay the best young golfer to come along since Jack Nicklaus.

With that in mind, I put my cards on the table: “Here’s a generational talent with charisma and global appeal who will instantly rocket Nike Golf into the big leagues. Not only are we coming to you first and exclusively, but we will give you the opportunity to own Tiger’s identity. The Nike swoosh on his shirt front and cap will be the only branding he displays – no other company logos on the shirt collar, chest, sleeves or back of the hat – a pure Nike message, front and centre, for all to see. Based on his unprecedented amateur achievements, every other company will want him. Nike can pre-empt them all, but it’s going to cost top dollar.”

Then, swallowing hard, I told Steve about $50 million over five years would get it done. No one else in golf – not Palmer, not Norman, no one – was earning anything like that for apparel and shoes, but through our tennis guys, I knew Agassi’s Nike contract was about $5 million a year, and from Steve I had a pretty good feel for Jordan’s compensation, so I thought, Why not go for it?

Steve’s first response, of course, was “That’s ridiculous,” but he didn’t say forget it. From the beginning he was straightforward about Nike’s strong interest. I figured the $50 million, while an overreach, wasn’t too far from where I might be able to end up, and that was a huge win not simply in sheer dollars but in the worldwide promotional power Nike would bring to the table. No other company in golf had the advertising budget or clout to help make Tiger a household name. On that score, Nike could have argued that it should pay Tiger less, not more. But they never did.

The other unusual part of my proposal on which they did not baulk (and I still can’t believe I got it) was all five years of Tiger’s compensation was guaranteed, regardless of his performance. I wanted Tiger to have financial certainty no matter whether he failed to get his tour card, missed Q-School, struggled initially or whatever. Nike would have been within its rights to ask for significant reductions in compensation for years two through five if Tiger failed to live up to the hype, but it never did.

Then there were the bonus clauses – dollar figures that were unprecedented in golf. I knew that Nike was used to paying bonuses to tennis players, so I checked the contracts of Agassi and other IMG tennis clients and was astonished to see six-figure payments for victories in Grand Slam events.

Again, I went for it with Tiger: $500,000 per major championship win in year one, increasing $100,000 per year to $900,00 per win in year five. Then I added the same bonus payment related to the Official World Golf Ranking if Tiger were to reach world No.1: $500,000 in year one escalating to $900,000 in year five. There were also provisions for ranking second to fifth ($350,000 in year one, increasing to $550,000 in year five) and sixth to 10th ($250,000 increasing to $350,000 in year five). These bonuses were based not on year-end ranking, as ranking bonuses normally were, but on the highest ranking achieved at any time during the year. Thus, even if Tiger were to reach the No.1 position for just one week, he would get that level of bonus. I guess no one at Nike bothered to check the contracts I had reached for Strange and Jacobsen a decade earlier – $5,000 for a major championship win in year one, $7,500 in year two. Had someone done so, Nike could have laughed my Woods numbers out of the room.

But no one did, and those clauses would add $8 million to what Nike paid Tiger between 1997 and 2001. When Steve eventually came back to me with a counter-offer of $40 million – $8 million a year guaranteed for five years – well, it was the most delightful compromise imaginable. Delivering the news to Earl and Tiger was the most sublimely satisfying moment of my career.

Then a few days later, as the final contracts were being drawn up by our legal department, something astonishing occurred – an attempt was made to sabotage the deal. By one of our rival agents? No, by Phil Knight.

Knight had a notorious hatred of agents, and on this occasion, he decided he would eliminate me. At the 11th hour he secretly dispatched a young Black Nike executive to the Woods home in California with an offer for Earl: “You don’t need IMG. Deal with us directly, and you’ll save the 20-percent commission fee.”

To Earl’s everlasting credit, he called right away and told me about it. Barely able to breathe, I waited to hear the outcome.

“I told the guy no,” Earl said. “I told him to go back and tell Phil Knight it’s important for me to be able to trust someone, and Hughes Norton is that guy.” Earl’s loyalty in that moment meant the world to me.

When it came to equipment, Titleist was the perfect home for Tiger. He had been playing a Titleist ball forever, carried a Cobra (owned by Titleist) driver and Titleist fairway woods and had no loyalty to the Mizuno irons in his bag, confident he could win with any brand of clubs. The timing was perfect to marry Tiger with Titleist and make him the spokesman for their new era of top-line equipment for better players.

I was so convinced that Tiger and Titleist were the ideal match that I had mentioned it to Titleist CEO Wally Uihlein on more than one occasion as Tiger was compiling his USGA Juniors and Amateurs. When the time for negotiation approached, we did most of the back and forth by phone and confidential e-mail.

I began by making Wally aware that we had been talking to Nike about some very big numbers. Being the super-prepared guy he was, he parried by reciting the statistics on Tiger’s then-lacklustre performance in pro tournaments. However, from the beginning there was a shared understanding that a deal was going to happen, and it didn’t take long to reach the numbers: $20 million for five years (with escalating bonuses like those in the Nike contract).

All that remained before finalising the contract was a meeting. Wally wanted to formalise things with a face-to-face meeting with Tiger, and this was a get-together that needed to be clandestine, so it was agreed that Tiger, Earl, Wally and I would meet in San Francisco. It was June 1996, and Tiger was just finishing up his second year at Stanford, so he was already out there. Wally flew in from Boston, Earl from Los Angeles, and I from Cleveland, all of us converging at a downtown hotel where Earl and Tiger had booked a suite.

I began by going over what the parameters of a deal “might look like if and when Tiger should decide to turn pro”. (At this point the decision had been made but not announced, and it was important for all concerned to stay within NCAA and USGA regulations.) Wally asked Tiger several questions about his specs and preferences about clubs, shafts, etc. Then he made a very strong statement, assuring Tiger that there would never be a moment when Titleist would ask him to play a product that he wasn’t happy with – the company would not rest until Tiger had exactly the clubs he wanted.

It was a great way to end the meeting, except that it wasn’t quite over. Earl had something he wanted to say. With a twinkle in his eye, he looked at Wally and said, “Now let’s get to the really important issue – when do I get my set of clubs?”

By late August, when Tiger arrived at Pumpkin Ridge for the 1996 US Amateur, everything was in place. I had surreptitiously arranged for him to get sponsor exemptions into most of the remaining PGA Tour events, and Phil Knight had laid on his private jet to take Tiger to the first of those events, the Milwaukee Open, where Nike had made arrangements at a hotel for a Wednesday morning press conference.

That said, Tiger had given no indication of his intentions. A week earlier he had assured his college coach he would be returning to Stanford in the fall, and at Pumpkin Ridge, when USGA president Judy Bell approached him and asked whether he would be playing in the World Amateur Team Championship scheduled for November in the Philippines, Tiger told her he would. Earl had been less circumspect – two weeks earlier he had told a couple of golf writers the decision had been made and would be announced immediately after the US Amateur, but he had also sworn them to secrecy, and the scribes had managed to hold their pens.

Late on Sunday afternoon, when Tiger holed the winning putt to beat Steve Scott on the 38th hole, it was hard to process what Tiger had accomplished. This kid won six USGA national championships in six consecutive years on six different courses – 36 straight matches against the highest level of amateur competition. Beyond his own unrelentingly stellar play, there was so much that had to go right. In any of those 36 matches he might have shot 66 yet been eliminated by someone who’d had the round of his life. A bad bounce here, a ball in a divot there, and the streak could have ended. The odds were so overwhelming, I couldn’t help musing that it was all somehow meant to be. I told myself I knew better, but maybe Earl’s bluster was legit: Tiger Woods is the Chosen One.

That evening, before leaving the course, there was one bit of business to attend to. The Nike folks had reserved a room in the clubhouse for a brief meeting. When I arrived with Tiger and his parents along with [Tiger’s swing coach] Butch Harmon, we were greeted by a smiling Phil Knight. With him was a guy I recognised from a visit to Nike.

“This is Jim Riswold,” Knight said. “He’s written some ads for me.” That was an understatement. Riswold, the creative director of Nike’s ad agency, Wieden+Kennedy, was something of a legend in the business, having created several iconic Nike commercials. They included “Air Rabbit”, pairing Michael Jordan and Bugs Bunny, and the “Bo Knows” series featuring Bo Jackson.

The most noteworthy ad Riswold would ever create was the one on the tape he was holding in his hand – the “Hello world” message that would signal Tiger’s professional debut. It would be shown for the first time at the press conference in Milwaukee, and Knight and Riswold were giving all of us an advance screening. At a signal from Knight, Riswold inserted his tape into the player, and all eyes turned to the television monitor in the room. As the video played – a collage of images from Tiger’s childhood and amateur career – a choir sang in the background and the words “Hello world” appeared on the screen. There were no voices in the entire 60 seconds, just Riswold’s script:

I shot in the 70s when I was 8.

I shot in the 60s when I was 12.

I played in the Nissan Open when I was 16.

Hello world.

I won the US Amateur when I was 18.

I played in the Masters when I was 19.

I am the only man to win three consecutive US Amateur titles.

Hello world.

There are still courses in the US I am not allowed to play because of the colour of my skin.

Hello world.

I’ve heard I’m not ready for you.

Are you ready for me?

To say it was unlike any golf commercial I had ever seen would be an understatement, and my first reaction wasn’t all positive. I had doubts about how the “courses I am not allowed to play” line would be received, but I figured Nike knew advertising. Beyond that, there was Earl’s painful history of discrimination – all those country clubs where he and Tiger had been made to feel unwelcome. With respect for that, I kept my thoughts to myself. When the screen went black there was dead silence in the room as we all tried to process what we had just viewed. Then Tiger said, “Can I see that again?”

After the second showing it was, surprisingly, Butch Harmon who spoke first: “That’s the best fuckin’ ad I’ve ever seen,” he said.

There was nothing anyone could add to that. The professional career of Tiger Woods was about to launch.

Two days later in Milwaukee I knocked on the door of the hotel suite where Tiger and Earl were staying. It was time to make things official. In my briefcase I had the two contracts from Nike and Titleist, which, when Tiger signed them, instantly guaranteed him $60 million. Tiger signed them both without comment, indeed without reaction of any kind. Curiously, he had always seemed almost indifferent to the money. Granted, a 20-year-old just beginning as a professional would have little or no frame of reference for the enormity of these contracts, but even when I’d tried to put the Nike and Titleist agreements in context – “Tiger, do you realise you’re now making four times what the current No.1 player in the game, Greg Norman, earns on golf clubs and balls and more than double what Greg makes on shoes and clothes?!” – his reaction was muted: “That’s not bad, right?”

The third contract he signed that evening was his representation agreement with IMG. It differed in significant ways from most of the contracts I had done, beginning with the commission structure. Working together with Tiger’s attorney, John Merchant, I had agreed to adjust our fees to a sliding scale similar to the royalties on a book contract: IMG would receive 15 percent of the first $2.5 million in annual merchandising income we earned for Tiger, 20 percent on income between $2.5 million and $5 million, and 25 percent on all income above $5 million. A second clause related to the term of the agreement. The base contract was for four years, from August 1996 to August 2000, but I had added incentives. If in any year IMG were to produce income for Tiger exceeding $16 million, the contract would be extended by two years to 2002; if we could produce more than $26 million, then the contract would extend another two years to 2004; and if we could produce $38 million, it would go one more year to 2005, a total of 10 years. We would earn all six years of those extensions by the end of 1997.

Editor’s Note: Hughes Norton would represent Woods until September 1998 when he was replaced by Mark Steinberg, another IMG agent. At the time Woods cited “overscheduling” as the reason for making the switch. Woods would generate $US4 million in fees for IMG in just the first year of their agreement, which continued until 2011 when Woods followed Steinberg to Excel Sports Management. Norton would leave IMG in early 1999 with a $US9 million severance package and a 10-year non-compete and non-disclosure agreement. Woods has earned more than $US1.8 billion in endorsements and prizemoney in his 28-year professional career and joined Forbes’ annual list of billionaires for the first time in 2022.

Adapted from Hughes Norton’s Rainmaker (Atria Books, March 26, 2024)

The Latest News

-

December 22, 2024Tiger Woods’ son Charlie makes a hole-in-one in the final round of the PNC Championship – Australian Golf Digest

-

December 22, 2024Tennis’ love match: Meet ‘Aussie’ Matteo Arnaldi and his Melburnian girlfriend

-

December 22, 2024GEORGIE PARKER: McSweeney was McStiff to get axed

-

December 22, 2024Chris Eubanks picks the ATP player he considers a real dark horse to win the Australian Open

-

December 22, 2024Time for the Swedish chef: Ikea’s furniture profits are down in Australia, but food sales are booming