Why is Tony Finau being sued? – Australian Golf Digest

- by Admin

- September 30, 2024

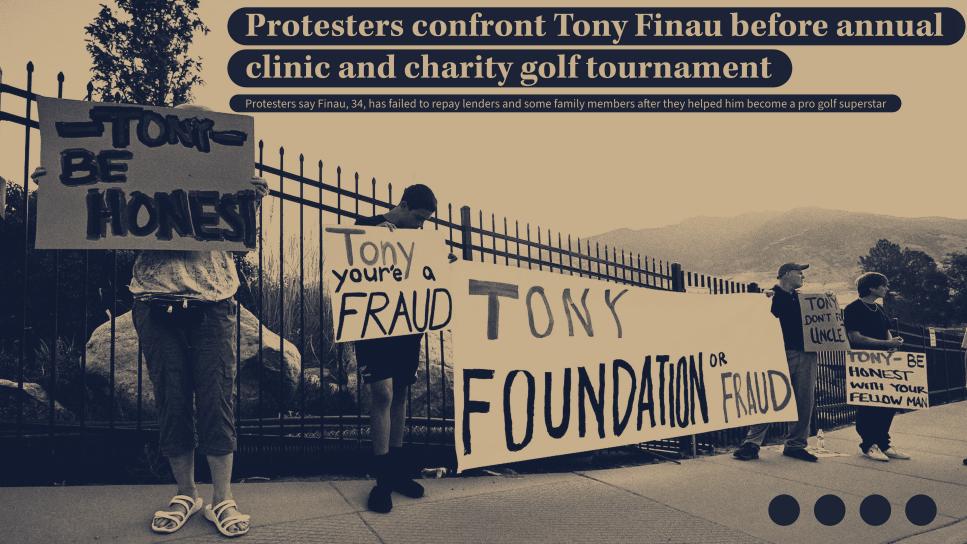

The protestors were stationed outside Oakridge Country Club hoping to see Tony Finau, and hoping Finau would see them.

Finau was coming to the Farmington, Utah course to host an event that would benefit his foundation. Yet a dozen or so individuals camped in the heat for two hours this past July to remind the PGA Tour star of the debts they say he ignored.

“It’s a story no one is telling,” protest organizer Rocky Bowlby said months later. “No one knows the real Tony.” To Bowlby, the real Tony was reflected in the messages scrawled on the demonstrators’ cardboard signs: “Keep Your Word,” “Pay Your Family Back” and “Be Honest with Your Fellow Man.”

One poster was hoisted above the rest: “Tony Don’t Forget Uncle Toa.”

Around 8:50 a.m., an SUV pulled up to Oakridge with Finau in the passenger seat. Cameras captured him looking in the protestor’s direction and the vehicle slowed as it neared the entrance. But Finau’s window stayed up, and the car never stopped.

Tony Finau’s story has been cast as the American Dream: A man of color emerging from the projects of Salt Lake City’s gritty westside to succeed in a white country club sport. “Growing up, there were gangs all around us,” Finau told Guy Yocom in a Golf Digest My Shot interview. “A lot of drugs, some crime, and a lot of peer pressure to get into that. Golf saved us.”

More on Tony Finau Explainer Understanding the legal claim at the heart of the Tony Finau lawsuit

Unable to afford regular course access, his father Kelepi “Gary” Finau set up a mattress against the garage door at their house to serve as a driving range for Tony and his brother, Gipper, and the family relied on others to provide the additional resources that are a staple for other aspiring golfers. From these humble beginnings Tony became a heralded amateur and turned pro after high school in 2007. Although he missed earning his PGA Tour card for seven-straight years, Finau’s talent—coupled with an undeniable fortitude and self-belief—could not be denied. After almost a decade of professional struggle, Finau eventually reached golf’s highest level, and made his fifth team appearance for the United States at the 2024 Presidents Cup, going 2-2 in the American victory. His unusual journey, along with an affable, warm demeanor, has endeared the 35-year-old Finau to fans, fellow competitors, and the media. In Golf Digest’s latest “Nice Guy” rankings that surveyed players, caddies, tour and tournament officials, Finau topped the list. “If I have a conversation with a person, and I leave thinking I’ve brightened their day just a little bit somehow, that makes me happy,” Finau said. This is the Tony Finau most of the public knows, one who was amplified in an episode of the Netflix reality series, “Full Swing,” which portrayed the battle between Finau’s career with his devotion to his family to an audience of millions.

A closer look suggests Finau’s story is far more complicated.

In the fall of 2020, Utah businessman Molonai Hola filed a lawsuit in Salt Lake City’s district court against Tony Finau and his father Kelepi Finau, seeking what Hola says was his $600,000 investment into the Finau family, plus $16 million—20 percent of Finau’s then-career earnings. Months after Hola’s suit was filed, another lawsuit emerged from David Hunter, a real estate mogul, film and TV producer and co-founder of Halestorm Entertainment seeking to recover what he claimed was his own investment.

Hunter’s case has already been dismissed, and Hola’s argument has been limited to a claim of unjust enrichment. But Hola’s case remains open and ongoing, and those legal actions produced extensive testimonies about business dealings with the Finau family. Golf Digest conducted a dozen on-the-record interviews with those involved, and spoke to several individuals who declined to go on record for legal reasons.

The series of lawsuits invite questions about the credibility of the accusers and their allegations. Given the Finaus already won against Hunter, a victory for Hola is very much in doubt. Still, the long list of grievances from people who used to occupy Finau’s inner circle draws a contrast to the golfer’s public persona.

At best, they suggest Finau has been unable to disentangle himself from the various unconventional measures his father used to jumpstart Tony’s career when the golfer was a minor. At worst, they expose Finau and his father to Hola’s legal claim of unjust enrichment, and claims by others who believe Finau serially went back on promises made.

While multiple conversations were had with Tony Finau’s representation at Wasserman and Golf Digest leadership regarding this story, Tony Finau ultimately did not participate in an interview. Wasserman’s legal counsel replied that “Tony’s official statement is that he is declining to comment given the pending litigation.” Likewise, Kelepi Finau did not respond to requests for comment.

Tony and Kelepi Finau addressed some accusations in a deposition given in April 2022. Those answers are included in their relevant sections.

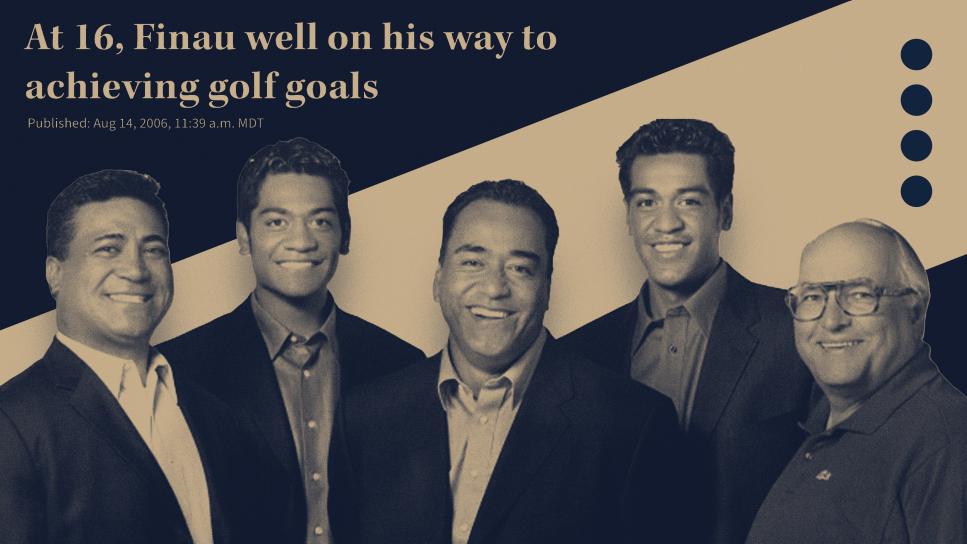

Molonai Hola (left) with the Finaus (Gipper, Kelepi and Tony) and Dieter Esch.

Molonai Hola says Kelepi verbally offered a 20-percent stake in Tony and Gipper’s future for immediate financial backing during a 2006 meeting. An initial $4,000 from that meeting beget a three-year investment in the family, and Hola says he has received nothing in return for his efforts. Hola admits there wasn’t a written contract with the family, but that the deal was a “handshake, tears and a hug.” The Finaus contend that’s because they don’t owe him a dime, and that if anyone is a victim, it’s them.

The lawsuits tried to collect on essentially the same investment, with each claiming that the investment entitled each plaintiff to roughly 20 percent of Tony Finau’s earnings and sponsorship. To date, Tony Finau has made more than $43 million in on-course winnings on the PGA Tour alone, along with millions accumulated in endorsements from Nike, Ping and T-Mobile.

“With my knowledge now, when I look at the contract that was put together for the Finau Corporation when it pertains to golf, earnings, winnings, different things like that, to me that is a bogus contract,” Tony Finau said in his deposition. “I’ve had a few things. But I know when someone’s taking advantage, and that’s what that contract was.”

A second investor, Hunter, said he had a similar arrangement with the Finaus, and in his case, he had a signed contract. He just waited too long to make his argument.

Hola, the Finaus and agent Dieter Esch formed “the Finau Corporation” in 2007 as an avenue to pay for the Finaus’ golf expenses and, eventually, what Hola believed would be the conduit for him to make a return on his investment when the boys started making money. Aside from a Callaway contract for Gipper and Tony, Hola was the main financial benefactor for the corporation. Court documents obtained by Golf Digest show the corporation racked up more than $532,000 in expenses from June 14, 2007 to Aug. 25, 2008, which included items as rudimentary as meals and gas, to flights and hotels for the boys for golf tournaments, to rent for the Finaus’ house. Hola says he began diverting resources from his other businesses, and eventually had to bring in one of his business partners, Steve Gasser, along with Hunter to secure a papered loan to keep the corporation going.

However, Hola says his investment was never recouped because the Finaus eventually sought to end their relationship.

According to Hola, the dissolution traces to the golfer’s relationship with celebrated instructor, David Leadbetter. The teacher had become wary of Kelepi’s meddling, and had requested limiting the father’s influence on Tony’s training. Since Hola was the one asked to deliver the message to Kelepi Finau, Hola says Kelepi retaliated by ending their agreement.

In a response to a Golf Digest inquiry, Leadbetter said he “does not recall” telling Esch that Kelepi had to go. In his deposition, Kelepi said he removed the boys from Leadbetter’s coaching because they were getting “frustrated” with the game. In an April 2022 deposition, Tony said he “did not enjoy” his time with Leadbetter. “I just became a little paralyzed with a lot of things he told me I needed to change in order to become a great professional. Almost made me feel like I had a really long ways to go.”

In 2009, the Finaus voted to dissolve the corporation against Hola and Esch’s wishes, and Hola said he understood why.

“If someone came to me and said, ‘You can’t be involved with your son,’ yeah, I’m going to have a hard time, so I get where Kelepi was coming from,” Hola says.

In his deposition, Tony Finau said he “can’t recall exactly” why he voted to dissolve the corporation. Regarding the end of his relationship with Molonai Hola, Kelepi Finau stated, “I don’t know how that came about or where nor why,” during his deposition.

Hola says he initially didn’t pursue legal action after the corporation’s disbanding for two reasons. The first was simple: at that point, the boys were scuffling on the mini-tours and weren’t making money. But he also said it felt counter to his initial motivation for helping the Finaus out.

Hola, who was well-known in Salt Lake City’s Polynesian community as a former mayoral candidate, says he was initially approached by Kelepi and his wife Ravena in 2006 after Tony had won the Utah state championship. Gipper was rumored to be even better, routinely outdriving Tony with 400-yard bombs. “I’ve got two Tiger Woods in my hands,” Hola remembers Kelepi proclaiming.

But the Finaus said they were cash-strapped. The family needed money for rent, broken appliances, medical bills, to say nothing of the boys’ golf ventures.

“There’s 60,000 Polynesians [in Salt Lake] because of the Mormon church, and a lot of us are poor,” Hola says. “I grew up with my brother, and I remember how hard it was for us.” Hola says he cut the Finaus a $4,000 check on the spot. He claims he took care of the rent, and eventually moved the family into a new home. He gave Kelepi a credit card with a $25,000 limit to pay for various expenses, and put Kelepi on payroll to give the family a stream of income after Kelepi left his job at Delta.

In his deposition, Kelepi said he didn’t “recall” getting a $4,000 check from Hola during their initial meeting, and that the credit card was through the Finau Corporation. Kelepi’s deposition did acknowledge a motion from a Finau Corporation meeting, however, where “Molonai Hola moved to continue to pay Gary Finau same current salary with benefits and increase his business credit card limit to $25,000.”

As Hola admits, it wasn’t strictly altruistic: He was giving the Finaus money under the presumed guarantee that Hola would be reimbursed when the boys made it big.

As a businessman, Hola has a mixed record. Court documents show Hola filed for bankruptcy in 2011 with liabilities totaling more than $5 million, including a number of lawsuits pending against his consulting firm in the early 2010s. Documents also show that Hola issued a series of checks from the Finau Corporation back to his Icon Consulting Group for approximately $400,000 shortly after securing the loan from Steve Gasser and David Hunter. In their court filings, the Finaus have argued this should cap any potential damages suffered by Hola to $198,724.39. Hola has countered that he had already shifted money from Icon to the Finau Corporation, and that the series of checks was to appease a government bond from his consulting firm unrelated to the Finau Corporation.

For a decade Hola says he did not bring up the issue of repayment—mostly because Tony had still not established himself on tour—until running into Tony at a charity event in 2018, where they agreed to grab lunch weeks later. When they eventually met over sushi, Hola asked for the money he was owed, and Hola says Finau agreed to invest in some properties Hola owned as compensation. Those investments never materialized.

In his deposition, Tony said that any potential money or investments to Hola should not be perceived as a repayment, but a gift on Tony’s part.

Hola says he didn’t hear from Finau for 14 months. The pandemic hit, and Hola, already with a string of financial woes, felt especially squeezed. He connected with Finau on April 2, 2020, believing it was time for the bill to come due. In Hola’s retelling, Finau agreed, and told Hola that he would be receiving $275,000 from Finau’s financial advisor, Scott Reed.

Reed, who was Finau’s financial adviser for four years beginning in 2016, confirmed to Golf Digest that Finau instructed him to send money to Hola in 2020, but he does not remember the exact amount. Reed added that Finau then called him within a couple hours and instructed him not to transfer Hola funds. “Didn’t tell me, didn’t give any context or tell me anything,” Reed says. “And I did what I was told.”

Reed said he was eventually let go in 2020. In his deposition, Tony said he fired Reed because “I wanted to go another direction,” later revealing he “investigated” Reed because of suspicions of missing money. Reed denies any claims of impropriety. In 2021, he was suspended from his industry for selling $3.5 million worth of unapproved private investments.

In his deposition, Tony said he tried to send money to Hola through the financial application Zelle, but the wire didn’t go through. He said he brought in his then-agent, Chris Armstrong, after Hola and his wife told him the transaction never came. Finau’s explanation suggested he had concerns about Hola. “I was fully intending to help,” Finau said in his deposition. “But it was no coincidence that the money couldn’t be sent. And once those red flags started to come, I knew I needed to get people that I trusted involved to get to the bottom of this because it started to sound like he actually thinks that I owe him money.” According to his deposition, those red flags included texts from Hola, a call from Hola’s wife and repeated calls from a person who identified themselves as Hola’s friend that Tony didn’t know.

Armstrong informed Hola in the spring of 2020 that Finau would not reimburse or compensate Hola. Only then did Hola decide to file his lawsuit.

“I said, ‘Don’t do this to me, Tony. I was there for your family when you didn’t have a house, when you got kicked out of your house. You had nothing,’” Hola says. “And then, at my most desperate, when I need him, he sends his agent to tell me he’s turning his back on me? At that point, I realized, he doesn’t get it.”

Throughout his deposition, Tony Finau expressed his belief that Hola took advantage of his family. Tony initially admits multiple times this opinion was formed through his father, but later in the deposition says he came to his own conclusion.

“As I’ve learned about what went on in 2007, 2008, 2009, that this was—we were looked at as an investment,” Tony says. “And the state of my game, there was supposed to be help. And when there were no more funds, then, not only was the state of my game in a terrible place, but we were starting from ground zero. So the assistance and help that was supposed to be there was not. It was not a pleasant experience in these couple years.”

Tony did not go into greater detail, only commenting that his parents questioned the accounting done by the Finau Corporation.

Although Hola lacks written proof of his agreement with the Finaus, several people who claimed to have similar dealings with the Finaus have come forward with their experiences to Hola’s case (but, to date, have not taken a legal route of their own against the Finaus). They include:

• Rocky Bowlby, who told Golf Digest he invested $150,000 in Tony and Gipper Finau from 2010 to 2014. Bowlby says his relationship ended because of a dispute with Kelepi over Gipper’s playing future (Gipper attempted several resurrections of his professional career but hasn’t played in a tour-sanctioned event since 2017). Bowlby, a former co-owner of a Fortune 500 dental-insurance company who became a Long Drive competitor, says he provided the Finaus with vehicles and a monthly income beginning in 2010, made sure all travel and tournament costs were covered, paid for an apartment and furnishings for Tony and his wife Alayna (who were married in May 2012), took care of medical bills, even let Gipper stay at his home for an extended time. Golf Digest has obtained a copy of one of Bowlby’s contracts with the Finaus, which—like those agreements claimed by Hola and Hunter—offered Bowlby a percentage of earnings and endorsements for financial backing. Bowlby says he never received compensation for his work.

• Frank Tusieseina, who says he originally introduced Hola to the Finaus in a declaration to the court, and later set up a new group called “Finau Enterprises” in 2010 after the Finau Corporation dissolved. Tusieseina is a Polynesian sports agent who produced a basketball reality show called “Who’s Got Game” for NBC Sports in the early 2000s. According to the declaration Tusieseina terminated his role in Finau Enterprises within months of his launch; multiple sources stated his departure was due to friction with Kelepi’s involvement. The declaration says Tusieseina raised $50,000 for the Finaus, which included his own money. In response to Golf Digest, Tusieseina acknowledged his investment and work with the Finaus, but otherwise declined to discuss specifics of his departure on record.

• Marcus Burbank, who says he was abruptly dismissed as Finau’s caddie in fall of 2014 after Finau had assured him he would stay on the bag when the player reached the PGA Tour. In his court declaration, Burbank detailed an incident in Boise, Idaho, in which Finau came to him in tears because Finau and his wife had got into an argument over his father getting money. “I consoled him for several hours and helped him through it to repair things with his wife,” Burbank says.

The Finaus did not address Burbank in either of their depositions.

• The Finaus’ former agent, Dieter Esch, who owned Wilhelmina, one of the largest talent agencies in the world, also appears in Hola’s case. Esch says he played a pivotal role in a meeting that was called in 2019 in Salt Lake City where he was asked to mediate between the Finaus and some of their alleged creditors. Esch brought a list accounting for all the money they felt the Finaus owed, along with a number—$1.3 million—that Esch believed could satisfy the creditors.

In interviews and in his deposition, Esch said Kelepi responded, “Over my dead body.”

In his deposition, Kelepi said he didn’t recall telling Esch or Tony anything like that. In his deposition, Tony Finau said he left the meeting when the talk of finances began, and that he couldn’t recall what he discussed with his agent about the meeting.

Following a failure to reach an agreement, Esch says he turned to Tony’s representation and remarked, “I can’t believe that you are going to let him walk into this trap.”

• Then there is David Hunter, who was a friend and partner of Steve Gasser. A year after the Finau Corporation dissolved, Gasser died of sudden cardiac arrest at age 46. Hunter purchased Gasser’s remaining pact from Gasser’s family for $25,000, which is how he became the sole owner of a no-interest loan of $495,000 to the Finau Corporation, which was transcribed on Oct. 9, 2008.

Tony Finau reached the PGA Tour in the fall of 2014, and the following summer, Hunter says he reached out to Tony about getting the initial investment back. The two met at Hunter’s office in Provo on a Saturday for three hours. According to Hunter, Tony said that came to a resolution. “And I was like, ‘Tony, I knew if we sat down for two minutes, we’d have this all resolved.’”

Three days later, Hunter received the phone call from Kelepi telling him the deal was dead.

When Hola’s lawsuit went forward, Hunter says he believed he could get his money back, so he thought, “Well, what the heck” and filed his lawsuit in May 2021. Unfortunately for Hunter, he lost his case in the trial court and again by appeal in February 2024, as the court ruled his statute of limitations expired.

“If you read the ruling, it essentially agrees I had a contract,” Hunter says. “The problem is, the court says that date began in 2007. I countered it was in 2015 after my discussion with Tony. I was in the right. The only wrong thing I did was I waited too long to sue.”

Molonai Hola’s lawsuit was set for an October 2024 trial date, one that would have coincided with the PGA Tour’s Black Desert Championship, the first PGA Tour event in Utah in 60 years. However, on Aug. 29, 2024, the judge delayed the trial, citing “unforeseen circumstances.” As of this writing, the trial remains without a date.

The Finaus’ side of the story—particularly Tony’s involvement or lack thereof—warrants consideration. Tony was a minor when the Finau Corporation was established and was not yet 21 years old when it was dissolved. Same goes with Tony’s business dealings with Dieter Esch. He was still of college age when Frank Tusieseina and Rocky Bowlby entered his family’s orbit. Repeatedly in his deposition, Tony asserts he was unaware of the financials and business decisions between his parents and their various backers, and had no say in Steve Gasser and David Hunter becoming part of the Finau Corporation through their loan. In many of the allegations, Tony is beholden to things done outside his purview.

The motives and backgrounds of the accusers also merit examination. Hola has a history of bankruptcy problems. Bowlby and Tusieseina had a falling out with Kelepi Finau after investing six figures into the Finau family. Esch—who in his deposition asserted the Finaus owed his agency $20,000—spent time in a German prison in the 1980s after his construction machinery business went insolvent. Scott Reed was an ex-employee of Tony Finau, as was Marcus Burbank, with Burbank (rightfully or not) attributing child-support issues to the end of his relationship with Finau.

There is Hola’s case itself. The previous judge, James Brady, cited two previous cases as possible guidance on Hola’s decision, and a legal interpretation of those cases would seemingly favor the Finaus. (Brady, however, is unlikely to continue with the case after its latest postponement, sources confirmed to Golf Digest.) Hola initially filed for breach of contract, tortious interference and unjust enrichment, but only unjust enrichment remains, which is far from easy to prove.

“The toughest element to prove in an unjust enrichment claim is typically that the benefit was not a gift and instead, there was an implied contract between the parties with the existence of real quid pro quo,” says Darren Heitner, founder of Heitner Legal, which specializes in sports and entertainment law. There’s also the matter of Finau’s celebrity, particularly in Utah. “Theoretically, justice is intended to be blind,” Heitner says. “The status of the parties should not, by itself, play a role in adjudicating a dispute on the merits. The reality is that triers of fact, particularly juries, can be influenced by biases and perceptions that are not always relevant to the issue.”

In short, accusations involving business, and former business partners, can be a messy affair. Conversely, the allegations against the Finaus aren’t just from ex-businessmen.

Rosie Afo, one of Tony Finau’s cousins, says she worked “tens of thousands” of unpaid hours for the Finaus as an administrative assistant. Then in her mid-30s, Rosie stepped away from her career as an event planner in Nevada in 2006 to help her family in what she thought was a temporary role. The corporation could not afford to pay Rosie for her services, but Rosie said there was a promise that she would be made whole for her efforts. When that corporation folded, Rosie was listed as the manager of Finau Enterprises; in his deposition, Tony said Rosie was made the manager because “she was someone we trust.” Rosie provided all the minutes from the Finau Corporation meetings to Hola’s lawsuit, along with the corporation’s expenses.

It was through her work with the corporation that Rosie discovered Molonai Hola expected a return of 20 percent of Tony and Gipper’s earnings. According to Rosie, Kelepi downplayed Hola’s agreement. Rosie also asserts the $495,000 loan from Steve Gasser and David Hunter had a role in the Finau Corporation dissolving. According to Rosie, Kelepi didn’t know Gasser had the power to demand a payment from the loan (and something Rosie said the Finaus never agreed to), so Kelepi began plotting an escape. In January 2009, Gipper and Tony were added as “directors” of the Finau Corporation, giving the family a voting majority. In April, the Finaus used their voting power to dissolve the corporation.

In his deposition, Tony said he didn’t know why he was given the title of director or what that role would have entitled.

Rosie said her relationship with the family changed not long after Kelepi’s wife Ravena Finau was killed in a car crash in November 2011. Feeling like she lost a sister—and feeling like her life had been disrupted too long—Rosie returned to Las Vegas. Rosie said she only decided to come forward with her story to the case when she learned that Tony agreed to pay the reminder of their aunt Sylvia Afo’s house mortgage, only to reverse on the deal.

According to Sylvia, it was her husband Toa who introduced Tony and Gipper to golf because Kelepi didn’t “know anything” about the game. Toa gave the boys a ride to the course and followed them during their rounds for encouragement. Sylvia testified in September 2023 that, “Toa was asked to quit his job with the State of Utah and caddie full time for Tony [after he turned pro]. At that point, Toa had been working for the Utah Department of Transportation for 22 years and was only eight years away from retirement. Toa forfeited his retirement, his salary, and his benefits to caddie for Tony because of his love for Tony and his belief that Tony could make it to the PGA Tour.”

Throughout their lives, because they moved so often, Toa stored the boys’ memorabilia for them. Toa obliged and kept building the archive as Tony progressed. Trophies, scorecards, photos, balls, clubs, posters, caddie bibs, even the tape Tony had on at the 2019 Masters after he dislocated his ankle during the Par 3 Contest. “Toa had it because he was the one that helped Tony cut it off,” Sylvia says.

In a September 2023 declaration to the court, Syliva said that when Toa was still working for Tony as a caddie, “Tony told him that if he ever made it as a pro, he would take care of him and he would never have to worry.” Sylvia alleges that Tony and his wife eventually agreed to pay the rest of the Afo’s mortgage as a nod to Toa’s help. Because Toa quit his job with the state, his family got put in a precarious financial situation, made worse when Toa was diagnosed with cancer. In her deposition, Sylvia said she put “90 percent” of the blame on Kelepi for this “because he told us many times that we would be taken care of, and we trusted him.” Still, in 2020 Sylvia says she and Toa approached Tony about those prior assurances; Tony told Toa, “I’m working on it,” according to the declaration.

But Toa’s health deteriorated. In October 2022, he wrote to Tony about their agreement, understanding he wouldn’t be around to see it honored. “You understand, from the beginning, the Commitments, Sacrifices, the Promises made,” Toa wrote. “We’ve talked about it for two years. To ease the burden and the worries for me.”

Months later, after Toa passed away on Feb. 2, 2023, Sylvia was sorting through medical bills and notes from her departed husband when she found the note to her nephew. In emails and texts that date back to 2020, the Afos had sent copies of their mortgage statement to Tony and his wife, Alayna, alluding to this alleged pact. Sylvia forwarded Toa’s original letter that month, along with a message of her own:

“[Toa] wanted to make sure that was done and not leave me with this burden. I’m struggling with this. I’ve been advised by my Legal Counsel to send this first.”

The response from the Finaus was swift. “We will NOT be honoring any promises or commitments that were claimed to be made by myself or my parents,” Finau wrote on June 30, 2023 from his wife’s email account. “Those claims were either made without my knowledge or were assumed because of our relationship all those years ago.”

Finau explained he and his wife were under no legal obligation, and that this email would be the end of their communication. “Sad that our relationship has come to this but we’ve had enough of the empty threats and passive aggressive communication from you. Proceed how you wish.”

In the reporting of this story, Golf Digest discovered Finau did forward as much as $20,000 to Toa’s family to cover funeral costs. Sylvia confirmed Finau sent payment, but also pointed out Toa lost more than $748,000 in retirement by giving up his government job to caddie for Tony.

Sylvia is protective of Toa, and was furious when she discovered the “Don’t Forget Uncle Toa” sign at Rocky Bowbly’s protest. “His story is not for others to tell,” Sylvia says through tears. “He loved that boy. He wanted what was best for him and Gipper. Toa was also fiercely independent. He didn’t ask for Tony to keep up his word for his own gain. He did it because he knew he was dying and wanted to make sure we were going to be OK.”

The sign was painful because Sylvia says Toa called Tony multiple times before his death, asserting the calls had nothing to do with the mortgage payment. Toa wanted to give the memorabilia to Tony and his kids as a final goodbye, with a message to keep building it with his family. But the calls went unanswered, and the boxes remain in Sylvia’s basement.

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com

The Latest News

-

December 22, 2024China’s Zheng to skip United Cup, needs ‘extra rest’ ahead of Australian Open

-

December 22, 2024India boycott press match after media battles

-

December 22, 2024Australian Open runner-up Zheng out of United Cup

-

December 22, 2024Nick Kyrgios results: Australian defeated in long-awaited comeback | Sporting News Australia

-

December 22, 2024China’s Olympic medallist Zheng to skip United Cup to stay fresh for Australian Open